Johan Grimonprez

Who owns our imagination?

With the poignant and swinging documentary Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, Johan Grimonprez once again impressed audiences and critics worldwide last year, and the second major retrospective of his work, All Memory is Theft, is currently running at the Zentrum für Kunst und Medien in Karlsruhe. We talk to Grimonprez, lecturer at KASK & Conservatorium, about the exhibition and the film, and about the research project he conducted at the school several years ago, in which seeds for both were sown.

During the conversation, Grimonprez moves back and forth between the large bookcase in the next room and the kitchen table where we are drinking tea. Meanwhile, the stack of books between us grows steadily; each volume heavily annotated. For Grimonprez, solid research always goes hand in hand with a seemingly inexhaustible associative drive. Everything is connected. Tickling and arms trafficking? Fireflies and UFOs? The power of imagination indeed is a recurring preoccupation: imagination to come up with other ways to live together.

Text: David Depestel

DAVID DEPESTEL

In the research proposal you submitted with Bram Crevits, several years ago, you talked about hope, among other things. At the time, you had just made Shadow World – about the grip of the arms trade on international politics – and you wrote that you were in need of something more hopeful, a focus on imagination, narrativity, empathy and tenderness, which had formed a countercurrent in the film. From that project, the vlog ‘On Radical Ecology and Tender Gardening’ eventually emerged?

I always like to find counterpoints in a story. When you address what’s wrong in the world, it’s important to also show which direction we could take instead. That’s why in Shadow World we had Raymond Tallis and Michael Hardt, among others, and that indeed provided the impetus for that train of thought for the vlog. Tallis talks there about the fact that you can’t tickle yourself, because the whole issue of the film can be boiled down to the fundamental question of how we relate to each other in society. That’s why I think the question of consciousness is so important. What connects us? Tallis argues that consciousness, and also identity, are inherently relational. The language we learn is a shared language and our consciousness always evolves in dialogue with others.

This is at odds with that world of arms trading, where everything revolves around privatising taxes, which basically amounts to theft of the commons. Resources are taken from the commons to make profits that only benefit corporations, the corporatocracy. So that counterpoint is in the film, including Vijay Prashad who is very critical of big world institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, that hold the knife to the throat of the global South. Michael Hardt is also in it, asking the question, with Machiavelli, about how to govern: based on fear or on love. Again, the question about what connects us and how we want to organise society. There is hardly any real discussion about that; what is really at issue is not addressed. So yes, that was the starting point of the vlog.

The vlog focuses on the commons, and the practice of commoning, inspired by David Bollier and others. We brought clips together in different modules, for example on the urban commons, where we think about urbanisation and how that urban space becomes a mirror of society. Look at Times Square – or our national airport in Zaventem: corporate logos everywhere and, hidden among them, one small project that an artist gets to fill in. Actually, that is the world upside-down; if that is our public imagination, what a poor state it is in. They should all be artists! Surely it is the essence that we should think about and display in the urban commons?

Another module is about biopiracy and seed democracy. Vandana Shiva is very important there, and we also invited her to KASK at the time. Why on earth is 60 to 70 percent of all seeds privatised and owned by a handful of conglomerates? It is absurd that organic farmers can no longer sell their untreated seeds because of an alleged risk of contamination. Because of the lobbying system, the big corporate conglomerates get legal texts passed that make it impossible for small farmers to sell. Setting up a seed bank, then, becomes almost illegal, while sharing something like that is essential. Vandana Shiva co-founded Navdanya, a seed bank largely run by grandmothers. They bring heirloom seeds to the seed bank and anyone can take seeds from it. Because really, nature is always a kind of potlatch that is very generous. Money was introduced into that only very recently and agriculture was always practised in groups. We often think that gardening requires a lot of work, but people used to do all that kind of stuff together: harvesting, building,... That’s a very different kind of economy, one where the social fabric is key — as in today’s ‘community gardens’, for instance.

The big question in the vlog project is how we relate to each other. And commoning is something that is simply practised in society, even within the family. There is always dialogue in the sense of: how do we relate to each other? That is commoning. And that, I think, is what has been lost within our current economy-focused society. So for each chapter, possible solutions are shown. Timebanking, peer-to-peer economies, ...

That material also forms the basis for a seminar I teach at KASK & Conservatorium in which we think together about how your own story represents a world view. Our stories are always connected to how we ourselves see our place in the world, so I first listen to what preoccupations there are in a particular group. For example, sometimes there are a lot of students thinking about ecology or gardening, trees or you name it. Or about how to engage in dialogue with another culture or subculture when making films, for example. That’s a module called ‘Othering’. I also have a background in cultural anthropology, and how to portray other cultures is a question I have always been thinking about. References there go from Jean Rouch to Chris Marker, and a lot of filmmakers dealing with memory, time and othering.

DD

That brings us to a second vlog on your site, ‘All Memory is Theft’, in which you focus on stories and imagination. That vlog also shares its title with the new major exhibition...

Yes, the vlog ‘All Memory is Theft’ is also set up in the ZKM. In the introductory text for the exhibition, I refer to Max Haiven and his book Crises of Imagination, Crises of Power. Because a crisis of imagination is also a crisis of storytelling. How can we represent how we stand in the world?

DD

‘Who owns our imagination?’, you ask in the intro to the vlog. That question might actually be a common thread throughout your work, no?

Just now, I referred to Times Square, a public space, an urban commons. All the tourists go there and what is reflected back at them is a corporate culture. A culture that is supposed to express in images how we think about, say, love or sex or identity. But they are all corporations telling those stories ... and over and over again, the bottom line of those stories is: buy some more. That means that the transition is complete from citizen to consumer. As a citizen you are supposed to think – or at least that is how it is usually interpreted – about how we live together, and politics is an expression of that.

To me the fact that someone decides to go to KASK and make films is already a political choice. You choose to start telling your own story; instead of just consuming, you also want to think creatively about how you stand in the world. The vlog starts with a section on ‘growing new stories’: we need to invent a different kind of stories, stories that will often be diametrically opposed to the ones we are served daily.

So in that text I quote Max Haiven: ‘there is a mourning for a lost future. Not for what was, but for what could be’. I also talk about how in my work, ‘history and memory function not merely as a means to recall the past but as a tool to negotiate the present, to reshape a shared future’ – with the emphasis on shared. ‘Memory after all is a form of collective storytelling.’

The title ‘All Memory is Theft’ actually turns everything on its head. It is a phrase from Greg Egan’s Permutation City, a science fiction novel in which a kind of piracy emerges around memory. Consciousness there is privatised and sold and traded by corporations. The last module in the vlog is ‘Who owns the future?’ ... When you see how technology is woven into society, our future already seems sold out to corporations. The same goes for the so-called ‘knowledge industry’, see for instance how close the Ghent biotech department is with the Monsanto-Bayer giant. DNA – ‘the building blocks of life’ – is already being privatised. The rich will at some point be able to buy more intelligent babies. In fact, we are already in a kind of science fiction story. Also, look at artificial intelligence ... why can’t all that kind of stuff be accessed as a commons?

My work is ‘Creative Commons’, anyone can download the films I own the rights to, as well as all the books. Everything is freely available online, but it can’t be exploited –Google or whoever isn’t allowed to appropriate those commons and charge for access to it.

DD

But since they are online they have already been used to train their AI systems...

Probably so, yes. Then again, that way AI may begin to realise that commoning also pays off. You can’t make anything work in society, including capitalism, if you don’t somehow share something, make agreements about which you ‘common’. Without Arabic numerals, there’s no capitalism.

History as a Way of Seeking Redemption

DD

We were talking about stories and imagination, and one of the great machines of – mostly conformist – narratives in our culture is, of course, Hollywood. Because of your Oscars nomination for Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat you found yourself in the middle of that ... Do you feel like a kind of viral particle there?

You have to realize that documentary really is an outlier within that whole Oscar thing; a few years ago they even wanted to abolish the category ... The so-called doc branch consists of about seven hundred voting members who have little to do with Hollywood.

That a film [No Other Land] that addresses the Palestinian issue won really is admirable. All five nominees looked very critically at a sensitive subject. The kidnapping of First Nation children in Canadian schools in Sugarcane. Shiori Ito addresses sexual exploitation in the highest political circles of Japan in a film [Black Box Diaries] that is completely boycotted there. And then there were [Porcelain War] about Ukraine and also Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat.

I did go along with it, also because I had invited Zap Mama [Marie Daulne] along. She is the voice of Andrée Blouin in the film, and had we won she would have made a statement there about the situation in eastern Congo. The private militia M23 had just invaded the region with the support of Rwandan troops. Zap Mama exchanged daily messages with Denis Mukwege, the doctor who has already cared for 80,000 raped and mutilated women at the Panzi hospital. That hospital is now in the hands of M23, and it is precisely those militias that are responsible for those rapes ...

So I thought it was important that she could have made a statement. In her dress and on the soles of her shoes it said ‘Free Congo’; she did make the press with that and the speech she had prepared was also read on the radio here in Belgium. So yes, I thought it was good that the flm could get a megaphone. If you want to be critical, you can also play it at a mainstream level. You have a much louder voice there, a much wider range. That doesn’t mean you should tune down your story. You can also be critical at that level, even if it’s a bit schizophrenic ...

But I was surprised by the response to this film, because the style is not obvious after all. With lots of text, even footnotes. The producers initially feared that this would get in the way of distribution but in the end, it was precisely that different style of storytelling – along with the music, of course – that has allowed the film to go mainstream. It has been released in Canada, in Mexico, in the United States, in South America, in Africa it is now playing everywhere. On 29 June, the eve of Independence Day, it will be shown again in Kinshasa. It has also been shown at the Andrée Blouin house. Suddenly people are talking about Andrée Blouin everywhere, early this year her autobiography was published by Verso. So she has finally entered history again, as she had literally been written out of it. Call it ‘history as a way of seeking redemption’.

DD

The film affects the viewer in a completely differen way than, say, Shadow World does. The latter can be almost paralysing – I totally understand why you needed a more hopeful project after that. With Soundtrack, you feel much more activated. Is that also the result of that thinking about other ways of telling stories and other kinds of stories? Because the subject matter is as horrific, of course, and the issue, as you also point out, anything but over. But you also show solidarity, genuine anger and outrage and what may or may not follow from that.

I always find it fascinating to have contrasts in a story. It breaks things open when you contrast them. Hence the combination of music and politics in the film. The political is all about ‘divide and conquer’, and the music is mostly about bringing people together. When the jazz ambassadors are sent out, of course they are used as propaganda, but even then Dizzy Gillespie goes and plays with local musicians wherever he goes – in

Syria, in Iran. They took to the streets, and very often they brought people together that way. There is the story that Louis Armstrong postponed the civil war because the Lumumba troops and the Mobutu troops secured his concert together... When Abbey Lincoln teamed up with the Women Writers’ Coalition to bring people together to stage a protest, that again grew from music. That anger is actually a dissatisfaction with what’s happening in the world; it’s not apathy like when you get knocked flat with revelations about the arms trade...

DD

The seeds for Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat also lie in the research and vlogs, correct?

That’s often how it works: the research in a vlog leads to an interesting story that starts to surface ... until I think there’s a film in it. At Documenta X [in 1997], the research for dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y was also present in the video library that was set up there. Already it included a ‘Close Encounters’ category in which I juxtaposed science fiction with exotica, as two forms of encounters with other cultures. H.G. Wells, the author of War of the Worlds, is said to have been in Tasmania with his brother, after the British colonial regime had wiped out the natives there, and his brother began to speculate: imagine if something like that happened to us, British ... That is supposed to have got Wells thinking about his story, the first in which aliens come to conquer the Earth. What if the coloniser is colonised: that’s how imagination can turn things on their head.

‘Close Encounters’ also became a vlog, and that may now eventually lead to the next project – TVDT // The Interspecies Parliament – about othering, via science fiction and how it is intertwined with the history of television. Some of that was already in Double Take, of course: how in the 1950s and 60s, rockets are used to launch television satellites into space, but are also mounted with nuclear warheads and racing to the moon ... Those beginnings of television go hand in hand with the closure of many film theatres. With the film industry in ruins after World War II, it is in those first big television productions like The Twilight Zone, Outer Limits and other science fiction that the imagination of the moment is expressed.

Something similar can be seen in the 1990s, when digital media and Photoshop first appeared. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the American imagination has to find another imaginary other and it is no longer James Bond versus the Russian spy, but Saddam Hussein becomes the bogeyman. Often that place is also left open during that period: The X-Files, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Independence Day ... Once again, you see the imagination revolve around the other, and the US is invaded by aliens. Kobarweng, my very first film, arose from the first question I was asked when I walked into a village in the Sibium Mountains on New Guinea: ‘where is your helicopter?’ I found that so fascinating because it makes you think about how people there were thrown into the ‘modern world’. That was through aircraft; the first Western geologist, quite literally the emissary of the mining and extraction economy was dropped there from a helicopter together with the first anthropologist, in 1959. In the film, that helicopter actually became another way of turning that on its head.

Who is looking at whom, that question, that relationship I find fascinating. The video library at Documenta X also included a very old colonial propaganda film I had found in the basements of [the RMCA in] Tervuren, Les Belges chez eux. In it, a Congolese anthropologist dubbed in a Western voice shows, so to speak, how Belgians live, in a very stereotypical way. Mother – because of course it is set in a typical nuclear family – gets up first, lights the stove with coal from the Congo, to make coffee that comes from the Congo. Then father

gets up, he has to go to work and washes himself very thoroughly with soap ... Breakfast is a happy moment, we are told, and you see the family sitting around the table in complete silence ... Very absurd all of it. Who is looking at whom, who is projecting onto whom? Anthropology is always relational, and thepower relations in it are very bizarre. Like when someone in Kobarweng says, ‘We never tell everything, we always keep something for the next anthropologist’ ... That power relationship is so fascinating to analyse.

DD

Was music part of the project for Soundtrack from the beginning of the process, or did that combination only impose itself along the way?

I knew Louis Armstrong ended up in the Congo in October 1960, and if you start digging further from there, you start to realise, ‘shit, but then ...’ That coup is staged and the assassination of Lumumba is plotted, the CIA is involved and it’s also the U.S. State Department sending out Louis Armstrong ... That in itself I found a fascinating story, that that music is deployed in a way you never thought possible. And when you start to look at things, you see a pattern. When Dizzy went to Syria, it also coincided with the CIA’s Operation Straggle. On the same night in 1963 that Duke Ellington performs in Baghdad, a coup takes place a little further down, at the palace ... Not a CIA plot, this time, but a counterplot because of a CIA set-up months before. The story is never far away. In 1956, the jazz ambassadors are expelled from Cairo when John Foster Dulles announces that the US will not give a loan for the Aswan Dam. Conversely, you can see how Dulles sends them out to hot zones to get certain things done. Dizzy Gillespie performs for Princess Pahlavi, sister of the Iranian Shah, in 1956. This was three years after the Shah had deposed Prime Minister Moussadegh with the help of the British and the CIA, because Moussadegh had insisted that British Petroleum honour the contract to return part of their profits to Iran. Dizzy also said it: ‘of course we were a political piece in the chess game of the cold war’.

And then there is someone like William Burden, about whom you could actually tell an entire story in Shadow World ... He was the president of MoMA but was also involved with the Pentagon and Lockheed, and at the time Congo became independent, Eisenhower sent him to Brussels as US ambassador. He was good friends with Baudouin, chums with Henri Spaak, and, of course, a secret CIA agent. Incidentally, he is also said to have taken some paintings from the embassy for the MoMA collection. The film also contains a reference to an article about how the MoMA board was basically the Who’s-Who of the CIA at the time ...

I find it interesting to throw that open and see how it is all intertwined. Burden was a big Magritte fan; at one point Mobutu says, ‘this is not a coup’ ... and all those ‘bad guys’ like Dulles, Hammarskjöld, all those prime ministers, they all smoked pipes and you constantly see Dulles telling lies with his pipe in hand ... with all of those echoes and associations, it is just too tempting then not to make that link.

DD

Door je montages, hoe je dingen naast elkaar plaatst, zit er ook altijd veel humor of speelsheid in je werk, als tegengewicht ook?

Humour can contain contradictions, you know ... You can address something very critically by making a joke about it but all the same you have addressed it. Like with a cartoon by Kamagurka where the caption schizophrenically contradicts the drawing. That’s how you break something open and how humour can introduce contradictions into a story. In storytelling, truth is very close to contradiction; stories that contain contradictions or dilemmas are always the best stories.

Poetry and politics, memory and theft

DD

Do you see a tension between the potential for ambiguity in artistic work, on the one hand, and activism, which may seem to call for more unambiguous messages, on the other? A lot of artists tread that line with their work in times like these, including many students here. With the musicians in Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, you seem to show the spectrum of possible relationships: from perhaps naively allowing yourself to be used to outright political protest ... How do you see yourself on that spectrum?

For me, those are not mutually exclusive. Politics and poetry can coexist, I think. There are some breaks in Shadow World, where Eduardo Galeano reads fragments of fiction that relate to what happens in the film. But initially, we had made some sequences for that with Manal Khader reading poetry by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. Eventually, that became the short film Two Travellers to a River.

Darwish was once asked why he did not talk about politics, and he replied that he wrote about love because he wanted to expose why he could not write about love. Politics comes into it anyway; every kiss is political – even the one in When Harry Met Sally.

Of course, there are degrees. dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y and Double Take were collaborations with fiction writers, Don DeLillo and Tom McCarthy. As a result, there is a kind of poetic layering in each. But Shadow World was a collaboration with Andrew Feinstein, a journalist, and then of course there are other journalistic parameters, then you have to back things up. What we couldn’t be completely certain of was written out of the film, and then the result naturally becomes more unambiguous.

This was much less so in an earlier phase, by the way, when the film was to rely even more on arms dealer Riccardo Privitera. Remarkable figure, he himself had contacted Andrew Feinstein because he thought it was a grave oversight that he was not mentioned in his book [The Shadow World: Inside the Global Arms Trade]! Arms traders usually don’t want to be in the spotlight, so we went to interview him several times – until he disappeared without a trace. He had constructed whole stories that turned out webs of lies. With that material, we eventually made the film Blue Orchids, but initially we wanted to construct Shadow World in such a way that as a viewer, you were totally immersed in the story of the liar until he is exposed at the end. My point was that Tony Blair and George Bush Jr. were of course the biggest arms dealers and liars of all, with their ‘weapons of mass destruction’. We thought about it for a long time, but in the end Andrew Feinstein and Chris Hedges, the former New York Times war correspondent who is also in the film, felt we’d better be straightforward, as they feared mainstream criticism would simply fixate on the one liar, even if he was matched by the other big liars. So that ambiguous narrator disappeared from it. Because indeed, as in Aesop’s proverb that opens the film: ‘We hang the petty thieves, and appoint the great ones to public office.’

But that layering was there in the other two films: for Double Take, McCarthy rewrote the story ‘Borges meets Borges’ as ‘Hitchcock versus Hitchcock’, where Nixon and Khrushchev start to resonate as metaphors in the dialogue of the two Hitchcocks. And in dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y, the fiction writer is set against the terrorist who turns out to be better at playing the media and has pushed him into the background ...

In Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, the layering is in the combination of very big stories being touched upon, and revealed according to a kind of thriller structure, with the poetry of music.

DD

In the film, you see people from all over the world taking to the streets ... except in Belgium, perhaps because people here were mostly confronted with propaganda? Meanwhile, the facts have been revealed, but the matter is still surrounded by a lot of silence...

Yes, at the time this was framed as just a kind of civil war in which Lumumba was simply murdered. The true facts only came to light much later, in large part because of Ludo de Witte. His book, The Assassination of Lumumba, was published in 1999, which of course was not that long ago. But the facts are known now, even if officially complicity is still not acknowledged. According to De Witte, we are even fairly lenient in the film in that regard.

The film begins with Lumumba saying he is not a communist, but an African. Because the Belgians framed him as a communist to get the US behind them. A few years before that, there had been the non-alignment movement, with leaders like Abdel Nasser, Sukarno and Kwame Nkrumah, who had to position themselves in relation to the superpowers. There was a kind of awakening in the global South, and Lumumba was part of that. Tragically, that whole movement was snuffed out by Lumumba’s assassination. That’s why the United Nations is so crucial to me, that’s where the balance was tipping because a strong Afro-Asian bloc was emerging that had the majority vote in the General Assembly — a political earthquake, really, that brought an enormous sense of hope. Of course Khrushchev tried to capitalise on that and get them into his camp. The criticism the film often gets is that we would glorify Khrushchev, but we do also show him as the ‘fat red rat wanted for murder’ on the Hungarians as well. That said, it is he who initiated the decolonisation resolution that the UN approved, who criticised Belgium’s role and also demanded that Secretary-General Hammarskjöld resign.

DD

That moment of hope speaks very strongly from the film, so much seemed possible, but of course as a viewer you already know what is coming…

Yes, then came that turning point. Kwame NKrumah, who wanted to set up a United States of Africa, was sidelined, Sékou Touré was also cut down by the French, and then you see that everything turns when there had just been such a flare-up of the global South that wanted to take control of its own destiny.

DD

You also show the continuity with what is happening now.

Nothing has changed. That’s why the Tesla and iPhone commercials are in the film. Those conflict minerals are the stakes of what is happening now with M23 in eastern Congo.

DD

In fact, that was my first association when I saw the title of the new retrospective: All Memory is Theft. I read in it a reference to our ‘memory devices’, which are dependent on that mining.

Indeed, it could also be interpreted that way. It was originally about consciousness, but if a state or company can buy more hardware, more and faster memory, that can also be seen as appropriation or theft. The same goes for historiography. That is also more or less privatised, or at least the imagination around it.

DD

The retrospective, what does that entail? There are screenings, you show archive materials,...?

Yes, but also drawings, photos, those piles of books over there also go to Karlsruhe, that is research material for Soundtrack – because of course, what ends up in the film is only a fraction. On the wall in the next room there, that’s the storyboard of the film, which has come down halfway but that is also being repaired and shown in the exhibition ...

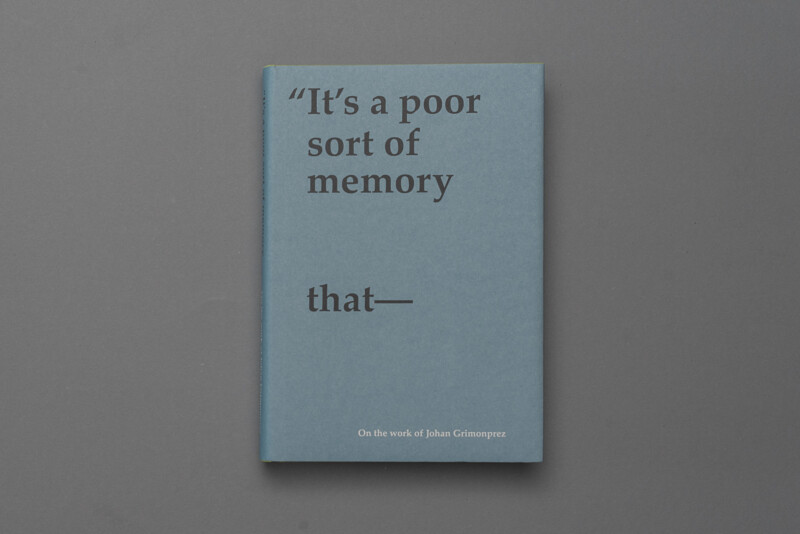

The vlogs will also be shown, just as at the time at SMAK [in the retrospective It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards, 2011-2012] you had themes linked to the films as focal points around which confrontations of different kinds of material were set up. The films are all shown, and there are a few interactive installations, such as Bed, where the deer jumps on the bed when someone passes. Drawings are less the focus this time, though there are hundreds of them in the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich. There are a few, though, that have to do with the next film – that series is called Pteroptyx Tener: synchronous flashing fireflies and is again about consciousness. The pteroptyx tener are fireflies that all flash on and off synchronously. So in a sense they have group consciousness ... The big question is how consciousness arose, and there are different schools of thought on this. Some say it emerged somewhere at the end of evolution, with some kind of feedback loop. Others, such as David Bohm, a quantum physicist turned philosopher, and David Chalmers of NYU, lean towards panpsychism. Chalmers writes that for consciousness to arise, it had to be inherently present. Perhaps consciousness then is the ground of everything, as in Buddhist thinking, and everything has consciousness in some sense. But how do you translate that: does consciousness then equate to knowing, or is it a feedback loop that corrects itself? Those fireflies are an important part of the research around that, and in my series of drawings I address the idea of othering again, with aliens and ants, trees and UFO invasions, and ultimately an interspecies dialogue...

The books will all be there as well, and I also teach a class at the academy that is in the same building there. For three days I will do workshops there, and that’s part of the exhibition – teaching is in fact an inherent part of my practice, all of it is interlinked: the research, the vlogs, the films, the teaching...