Tropes / In Conversation: a recap, with new work

With a new book and a gallery exhibition, KASK & Conservatorium teacher and researcher Ives Maes is marking the end of his post-doctoral project ‘Forbidden Fruits Create Many Jams’. Both shed light on the major evolution Maes’ work has undergone over the past decade, as well as on the motifs that recur throughout his work. More than ever, Maes feels he is being very open about himself in his recent work, but those wanting to find a clear and unambiguous message should look elsewhere.

The first thing you see as a visitor to Ives Maes’ exhibition Tropes, even before you enter Gallery Sofie Van de Velde in Antwerp’s Nieuw-Zuid neighbourhood, is a large cardboard panel, like the packaging of your flatpack bookshelf. This installation may seem slightly out of place for those unfamiliar with Maes’ earlier work. Seemingly outside the exhibition, shoved to the side and half turned away from it, the only spatial work also: does it belong to the exhibition? Well, yes it does, because it turns out to be a type of refugee shelter — specifically designed to quickly provide easily produced (and recyclable) temporary accommodation for refugees — that Maes has used before, in his project Recyclable Refugee Camp from 2008. Maes’ work has evolved dramatically since then, but certain elements keep returning, like reference points, mutating and accruing more and more associations: they are the tropes from the title of the exhibition: recurring motifs — but also metaphors.

The most striking motif here is that of refuge or shelter. But anyone who reads the conversation between Maes and curator and author David Campany in the new book — which has the perfectly straightforward title Ives Maes & David Campany in Conversation — knows that since Maes’ in-depth research into the relationship between photography and architecture the caves, shelters and hunting hideouts also always refer to the original camera obscura of the photography pavilion.

In his doctoral project (2012 – 2018), Maes made a thorough historical study that took in the first optical experiments in dark rooms as well as the CERN particle accelerator, via world fairs and the work of some of the most influential artists of recent times, in a way that also made clear the relevance to his own work. These case studies and interviews with the likes of Dan Graham, John Baldessari and many others are still awaiting wider publication, but the book that is published now already provides a fascinating insight into some of the conclusions from more than a decade of artistic research. It has become an extremely fascinating document — both visually and in the dialogue — which above all makes clear how intertwined research and artistic practice are for Maes.

The focus on photography and spatiality culminated six years ago in the Sunville project. There, Maes transmuted work with a very personal background into a series of hybrid works that hovered between alienation and nostalgia; review and revision, and with their curved frames and integration with sculptural elements, also between photography and installation. The explicit aim of the research project that followed Maes's doctorate in the arts, entitled ‘Forbidden Fruits Create Many Jams’, was to further explore this hybridisation. Maes based the project’s initial pitch on a whimsical anecdote: a fortune teller had assured him that he had been a 19th-century painter in a previous life. A painter, in fact, who had attempted to flee photography’s omnipresence and retreat to a tropical idyll to reinvent his painting practice. A flight that seems completely impossible today ...

Maes: “No, now there is no escaping it anymore. But even back then, photography was already very present. The Kodak Brownie was already around, with one hundred exposures per film. The printed press started to work with it, and the impact must have been almost incomprehensible. The veracity of painting had also been completely cancelled out by this new medium, which provoked reactions such as impressionism. In a sense, many of these artists wanted to escape modernity, and therefore photography as well. Escaping to ‘unspoilt worlds’, although once they arrived there they quickly realised that these worlds were not so unspoilt after all — and they also contributed to ruining them. But that funny incident with the fortune teller did encourage me to make a clean sweep of my work and start over, to feel completely free. And when I felt like starting to paint again, I would just paint.”

Reflections on the work and thought process that resulted from this can now be found in the conversation book, with a selection of remarkable artistic results in the Gallery Sofie Van de Velde. A crucial step in that process was to translate the interaction between architecture and photography that Maes had described in his doctoral thesis back into a camera obscura pavilion, “the archetype of the photographic principle” of which the camera is basically a miniaturized form: “I didn't want to use the pavilion just as a recording and developing booth, but also wanted the resulting photo to be an integral part of the architecture. That became Camp, in Watou (2021), which can also be seen in the book. The photo, on a wooden panel, is really an architectural component there; if you take it away, the pavilion collapses. The works on display here are a continuation of that concept.”

Indeed, in many cases the photos were taken with a so-called pinhole camera, in which long-term direct exposure through a tiny opening directly onto a light-sensitive emulsion leaves an inverted and negative image. Not quite an escape from photography, then, but an exploration perhaps of the possibilities of this atavistic impulse. By leaving out lens and digital post-production in favour of the physical essence of an architectural camera obscura, the idea of directness can arise, but Maes immediately appears to call into question again photography's claim to truth as the historically inspired technique looks irrevocably artificial — paradoxically, much more so than the digitally produced images with which we are oversaturated every day. This is reinforced further by the use of paint on the wooden panels, the brightly coloured metal frames made of powder-coated construction materials, and the fact that for other works the pinhole method was simulated with UV printing.

Maes constantly injects this kind of hesitation into his work, not only with regard to the truth claim of photography, and not in the least with regard to the nature of the motif, that trope, of the shelter. The cardboard shelter at the window turns out to have been used as a camera obscura for one of the works, resulting in its remarkable triangular shape. The plants photographed by the box evoke a kind of ratty park edge, while in another work a little further on, a banal ‘tropical’ houseplant adorns the frame. A large grid fence raises questions about interior and exterior space, a hunter’s hideout that lights up eerily in negative does so about the direction of the gaze, and about what and who exactly requires shelter. No explicit reference to exoticism is made, but it is clear that the shelter, of the ramshackle cabin or of nature, can never simply be idyllic. Every paradise is not only artificial but also ephemeral and ambiguous.

Parts of the dismantled Watou pavilion were previously on display during Maes’ previous exhibition in the same gallery. That show was the first to focus on revealing some of the motifs throughout Maes’ oeuvre, with work that was originally unrelated to the KASK & Conservatorium research projects but gradually became intertwined with them.

“By being stuck at home during the lockdowns [during the Covid-19 period], I started to dig out my analogue archive to digitise it. I came across a lot of images that had not been important, never intended to be used in my work except perhaps as inspiration. But they made me notice common threads running through my three major projects up until then. No matter how different the themes and execution had been, the ruinous and the ephemeral were always present. Refugees, world fairs that appear and disappear, my own village and surroundings as I remember them ... The connections between them began to strike me, and I decided to show those in this and in the previous exhibition.”

The idea of the cabin or pavilion is a constant in the series, but Maes did not allow himself to be pinned down to a process or a set of principles. “I felt like I was making up too many rules again and that hindered my freedom, and not just because the process is quite expensive, with a slim success rate moreover. Some of the archive images have simply been scanned and printed digitally. With painting as well, I just wanted to feel unrestricted ... here and there you can see traces of previous prints and layers of paint that have been sanded down, and that yields fun, unexpected results. The same goes for the brightly coloured frames, with that Meccano-like effect; I just wanted to do what I felt like doing, what worked with the images. The frames give some of the images colour without them being coloured in. By that point I felt the freedom to experiment fully.”

As an installation artist who works with photography, Maes also seizes the liberty to fully focus on the materiality of that medium. He and Campany discuss this extensively in the book. “The medium is very encompassing and documentary photography is only one aspect of it. The meaning of images is rightly given a great deal of attention, but as an artist I also shift my attention to their materiality. I think a similar movement is taking place as with pictorialism in the past, when artists who felt beset by the omnipresence of photography tried to work in a more hands-on way and produce unique pieces. And now that smartphones are so prevalent, with decent quality images, artists who work with photography are also focusing more on materiality again, making unique objects to be able to make a difference with that abundance of images. And yes, that also has to do with how the art market works. Prices of art photography have plummeted, and that has a lot to do with the idea that the photo is mechanically reproducible. It is a cycle, a silly debate that keeps popping back up and it’s rooted in the invention of the medium itself.”

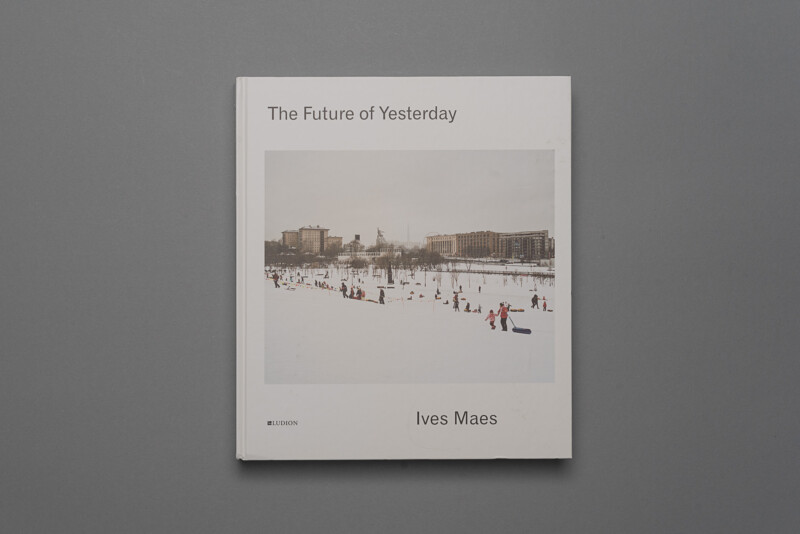

The cardboard ‘box’ is the only installation element in Tropes — “We tried, but it was too much to put the pavilions in the room. It just didn't work.” In a future museum show, that aspect of Maes’ oeuvre will be more visible again, and the installation view is also an important theme in the new book. The books Maes made around The Future of Yesterday and Sunville largely ignored that dimension in favour of a more narrative effect.

“There were many installation views in Recyclable Refugee Camp, because almost all of the works there were sculptures and installations. But I have always been very aware of the difference in meaning of those images, of a reproduction of a photo and an installation view with the same photo. For this new book, the intention was to let those installation views take precedence, because they were so absent in the other two books, but also because they all emerged from my archive. Regardless of the themes of the various projects, the new book also shows my development as an installation maker.”

Due to the nature and origin of the images in Tropes, this series also looks back; it is retrospective, but not in the sense of a clear career overview. How current knowledge shapes our experience of our own past and of our environment, or how past views of the future continue to loom like a parallel world behind our own, were questions that made previous work by Ives Maes so poignant (in Sunville and in The Future of Yesterday respectively). Similarly, in Tropes nothing really is what it seems.

“Some images are nice and fun, while others are rather disturbing ... the combination should be somewhat unsettling, I think. The whole communicates something about who I am and what I have to say. It is a difficult exercise not to talk about something specific that is separate from myself — such as world fairs, my village or a refugee camp ultimately were. Here I show everything. With Sunville, I really needed to distance myself in order to be able to assess the quality of the images. By taking that distance, I realised that I had the right images to experiment with presentation, which led to the curved frames. The images were abstract enough to be able to take that. The development of that presentation took some time, and the doctoral project was very valuable in that respect. At the same time, however, I built a new barrier with that research because it allowed me to talk about anything but myself. And that is what I do with these works, here I do show myself, or at least that is what it feels like. When we were installing this exhibition, I felt that typical trepidation, that fear of revealing too much of yourself. It had been quite a while since I’d felt that way, but it was much needed.”

Text: David Depestel

The book, published by Art Paper Editions, will also be available from the publisher and in the Kunstenbibliotheek from then on.

The Future of Yesterday (Ludion, 2013) and Sunville (Ludion, 2018) are also still available at the Kunstenbibliotheek.