Feminist education – the feminist classroom – is and should be a place where there is a sense of struggle, where there is visible acknowledgment of the union of theory and practice, where we work together as teachers and students to overcome the estrangement and alienation that have become so much the norm in the contemporary university. Most importantly, feminist pedagogy should engage students in a learning process that makes the world “more than less real.”

bell hooks, Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope

The convergence of feminism and curating has a rich history, rooted in the early days of the feminist art movement in the late sixties in the United States and the United Kingdom (the dominant locations for the movement's early development). In 1971, the art historian and curator Linda Nochlin published Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, in which she linked the imbalance between male and female artists to the organisation of education and institutional structures. A year later, in 1972, artists Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro organised the first feminist exhibition, WomanHouse, as part of the Fresno Feminist Art Program.

While these initiatives initially arose in response to the underrepresentation of female artists in exhibitions, art collections, and education, the focus has gradually evolved to encompass various feminist perspectives in curating. This includes building and deconstructing archives and narratives, developing new interpretative frameworks, and identifying structural inequalities within the art world. In recent years, curating has increasingly engaged with evolving concepts of citizenship, politics, and public participation, especially in the context of social justice and activism. This shift has been informed by a wide range of feminist viewpoints, including Black feminism, decolonial feminism, ecofeminism, hydrofeminism, crip feminism, and transfeminism. These theories have introduced crucial tools and concepts like care, intersectionality, and situatedness, offering a critical examination of power dynamics and revealing the intertwined layers of domination and marginalisation.

Today, intersectional feminist thought and action advance ideas of equality, freedom, and care, extending beyond traditional gender distinctions. This ethos is reflected in the art field as well. While new developments in the arts rapidly influence curatorial practice, they do not always permeate education and its methodologies at the same pace. How can intersectional feminist strategies and perspectives be integrated into curatorial pedagogy, aligning with the evolving curatorial and cultural landscape? This may involve reevaluating traditional educational barriers through a feminist lens, establishing an educational environment that embraces marginalized perspectives. It would be a space where participants actively contribute to the program's content and where power imbalances in knowledge creation are critically examined. Additionally, there may be a preference for teaching affective, experiential, transdisciplinary approaches to curation over more representative forms.

Feminist pedagogy, rooted in feminist theory and critical pedagogy, draws inspiration from thinkers such as Paulo Freire, Peter McLaren, Patricia Lather, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Ileana Jiminez, and Audre Lorde, and emphasises the shared power dynamics within learning environments. It recognises that knowledge is socially produced through collaboration and interaction, rather than being individually acquired. This approach seeks to connect social justice with learning, creating a community where students and instructors co-construct knowledge while acknowledging diverse identities and experiences. By facilitating awareness of power dynamics within the classroom, feminist pedagogy empowers students to recognise their positions as holders of knowledge, thereby expanding the educational experience. Finally, it is worth considering the interplay among education, parenthood, reproductive labor, and childcare. As bell hooks advocates in Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope, a direct confrontation with reality can be a starting point for curatorial education, moving beyond mere exercises or speculative questioning to look into real situations that illuminate the complexities of the world.

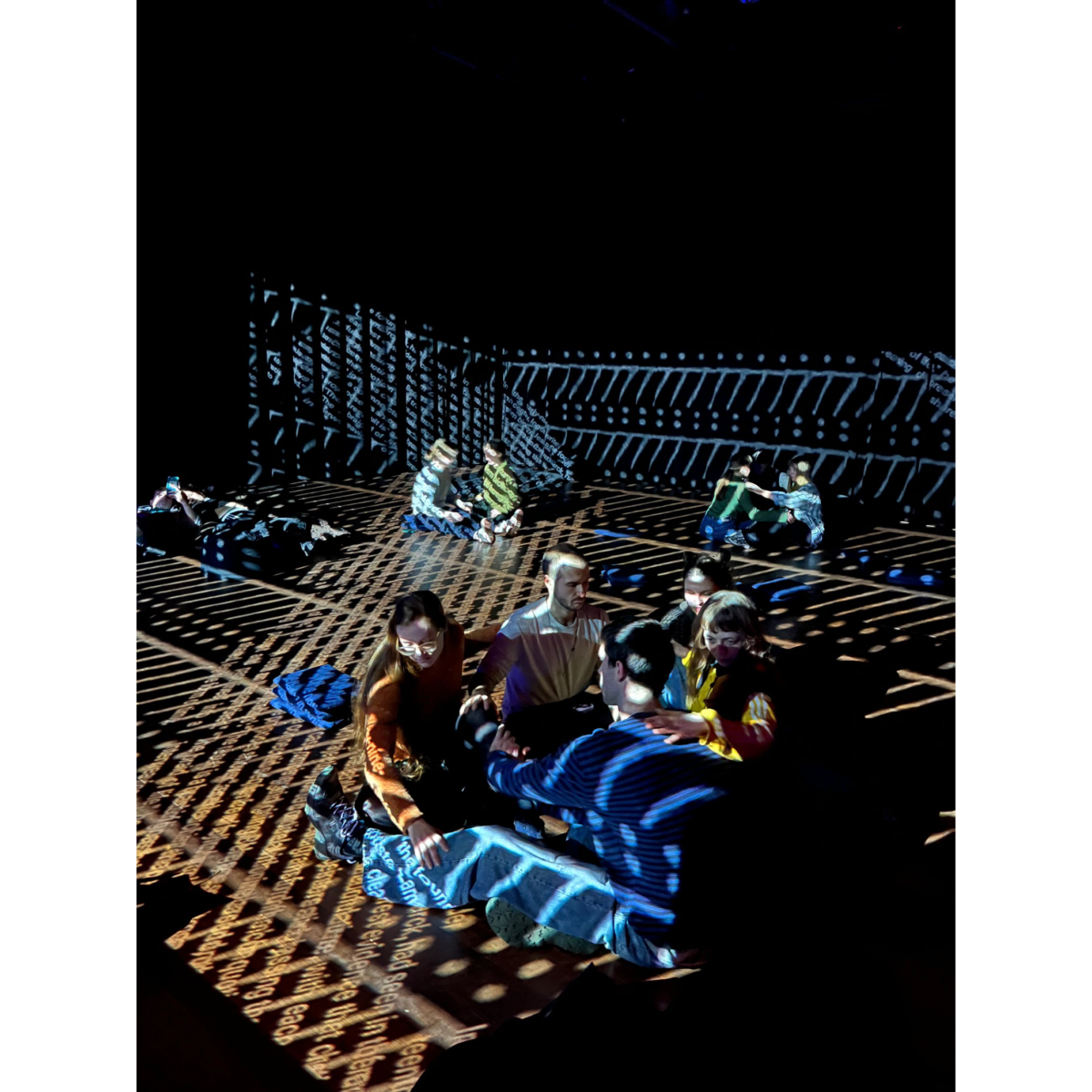

The research addresses pedagogical and curatorial concerns through a series of book reviews in De Witte Raaf and experimental masterclasses focused on feminist, embodied, and decolonial curatorial practices. These masterclasses emphasise interdisciplinary and cross-institutional collaboration and exchange. The project culminates in a two-day assembly organised in partnership with Sonia D’Alto, Jana Haeckel, and the Archival Sensations Research Cluster, which will produce a code of practice to further inform the future of curatorial studies.