Lotte Toko Lelo Maes

Who Am I Without You Mister Man?

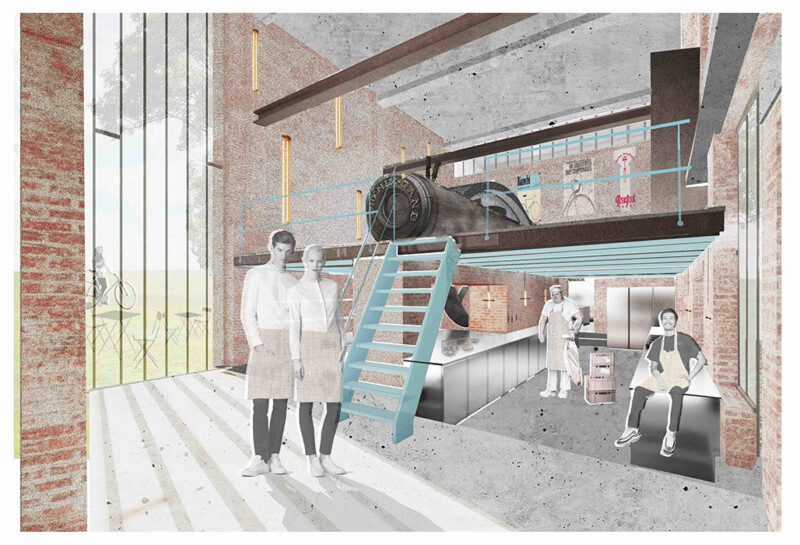

When questions, habits and frustrations prevail, visual arts can provide support in processing and confronting them. This process starts from my own body, not as an object but as a canvas, as a room for exploration and confrontation. Through performative and documentary self-portraits, I question the dynamics between men and women, and how power, gaze and fantasy nestle in images. What emerges are not mirrors but encounters: images that confront, break, repair and start anew.

Who Am I Without You Mister Man?

This question continues to echo and leads me to a second, vital question: can one philosophise about the “original” form of a woman, and can it be captured? What I learn along the way is that representation is not a mirror, but an action. Every image does something. It confirms or breaks a norm, it seduces, tames or disturbs. Representation ≠ reality.

That ethic is relational. A photograph is not a trophy that you “take”, but an encounter that you maintain. Who is looking? Who is responding? Who decides what remains visible and what does not? I am learning to express and share my position. Sometimes that means intervening less. Sometimes it means framing together, deciding together not to show. Sometimes the most caring choice is invisibility.

We live in a time that likes to congratulate itself on progress. Women are allowed to study, work, speak, be visible. The shop window of equality is full, but behind that glass, the foundation remains the same: a patriarchal structure that continues to regulate, tame and portray our bodies as if freedom has already been achieved. As if we no longer need to resist. That illusion is dangerous because it makes criticism suspicious and struggle unnecessary. As if there is nothing left to gain, while inequality is becoming more subtle, deeper and more vicious, embedded in language, in the media, in images.

My voice is not here to whisper, but to disturb. To scratch away at the self-evident nature of that “resolved feminism”. Because as long as the male gaze is still the standard, as long as representation reduces women to function or decoration, as long as society prefers to sell “empowerment” rather than relinquish power, nothing has been resolved.

On the occasion of my graduation, I wrote a manifesto. It ends with an attempt at direction, not a law. images that refuse. Refusing to be viewed carelessly, refusing to be possessed. My own body is both canvas and conflict in this; it bears the remnants of previous gazes and wonders: can I show without revealing, be visible without being understood? Perhaps that is enough. Perhaps that is a beginning.

Name your position, for whom and with whom do you create? Let post-production breathe, avoid putting smoothing over meaning. Look for the details, not to magnify them, but to listen to them. Respect illegibility, do not show what does not want to be shared. Share your doubts, and let them give direction.

And the “original form” of a woman? I don't believe that can be captured as a form. Perhaps it lies not in the photograph, but in the room between us, in the choice to look back, to slow down, to not want to know everything. If photography can do anything, it is this: not capturing, but letting go.

Therefore, photographer, if you insist:

Only photograph her if you do not reduce her to a body without a voice.

If you do not colour her to your liking, do not light her skin until it becomes untrue.

If you do not smooth her forms in the name of beauty.

If you do not tame her gaze, do not direct her posture.

If you respect her boundaries, even if they cannot be explained.

If you understand that even consent is fragile, changeable, revocable.

If you know that every choice she makes to be naked, to remain clothed, to be absent, is a form of direction.

If you don't talk about “working with women” without questioning your own position.

My writing echoes bell hooks, Susan Sontag, VALIE EXPORT, Linda Nochlin, John Berger, Margaret Atwood and many others who have given me the words to continue speaking.

My own body, in my work, is both canvas and conflict.

It bears the remnants of gazes that preceded me.

It wonders: can I exist outside of interpretation?

Can I show without revealing, be visible without being understood?

My work answers, probes, sabotages.

Perhaps that is enough. Or a beginning.

Photography, if it can do anything,

then it is this:

not capturing,

but letting go.

Liene Aerts

“Every image does something,” you said. They do indeed do something, they move me back and forth. I stand here and look at you, at where you stood then, and write down what the room between us tries to tell me. I feel beyond the single image and try to read “the moment” in its actual expanse and complexity. During the silences, you hear ordinary life continuing, awkwardness scraping along the walls. The situation, your presence and the self-timer tempt to ask a question or react, provoking mistakes and coincidences. After the first photos, I pause and look around. Details echo, glances are exchanged, find mine, and I feel their finding each other as a judgement against the one alone. I see you disrupting time, and much more, in these micro-worlds. Jammer and sponge, you are there, but you are also not there.

I move and choose sides in the alternating protection and shielding, explicit and implicit, minimising and exaggerating, relationship and dissociation, introversion and extroversion, framing and selecting. Together with you, I touch on things that are difficult to put into words, but which can be felt very keenly. I pick up on the sabotage that presents it as a game or a sport. You step into their world, with your bare skin as the ultimate fragility. The white flag flutters on the green field, contrasts glisten, they in white polo shirts, you in black underwear, we who adapt to the prevailing norms of the environment. Here, the mechanics of looking at work. I feel the care of the car mechanic who gave you a clean sheet of paper to put under your feet, but I also think I see the opposite in the piss that finds its way between your toes at the butcher's and the cigarette smoke that is blown over your body. The smoke finds its way, creating haze, pores and grain. A man was sitting at the bar with a friend, but the friend stepped out of the picture and left his full pint behind? The barber plays his work, there are no customers in the picture, a playful mop of shaving foam lands on your nose. One eye fixes on your backside. A lot is going on behind your back, walls are closing in around you, a grab crane dangles above your head. You steer where you feel something, but I get the feeling that more is coming over you anyway? So you let go more than you hold on to, thereby becoming your own porous object of study? I read doubt on your face. It is precisely this not knowing that gives shared direction and makes me smile.

Dear Lotte, I see a visual process of studying and graduating, seeing and counter-seeing, neither denying nor confirming, jumping into free fall, a beautiful field of tension!

text: Lotte Toko Lelo Maes with a concluding personal view of the work by Liene Aerts

photos: Lotte Toko Lelo Maes