Lore De Schutter

on the status of language

Lore De Schutter will soon graduate as a master of graphic design. As part of her thesis, she wrote an investigative artist's text in which she examines the ways in which Dadaism influences her practice. After all, she, too, likes to pluck bits of text from reality to extract building blocks of something new. By way of amuse-gueule, you can read an excerpt below. The curious will find her work at the Graduation exhibition July 1 through July 4.

I could begin this section by writing that "language is more important now than ever," but frankly, I have no idea. I can only comment on the times in which I myself live and experience language. What I do know is that language is everywhere: newspapers, radio, TV, books, billboards, magazines, posters, graffiti, logos, window drawings, social media, movies, neon lights on the street, conversations, music, whispers... (this list is far from complete and is being added to all the time). Because of the speed at which new things emerge in this day and age, it is inevitable that language changes as well. New concepts, translations and meanings are emerging, new ways of communicating ... with the digital medium leading the way. We take words from other languages and transform them into a Dutch word, or "Englishize" our own language. Old-fashioned terms are no longer used and new terms make their appearance in dictionaries. Even age-old grammar rules are being modified, much to the displeasure of many. Even within the same area, there are differences in language and miscommunication can occur because of a different sound or a word that has more than one meaning. And then there are dialects with words that are incomprehensible on one side of Belgium to the other. The diversity and richness of language appeals to me enormously and does not let me go, playing with language and wordplay remains inseparable from my own practice.

Sometimes I feel myself a writer while reading. Then I read Borges, for example, and there is something in me that feels like I am the author myself. As if, without asking, he has put my thoughts down on paper. Do I dare compare myself to a great writer, poet, thinker like Jorge Luis Borges? Is it not too bold to even dare to think such a thing? Perhaps deep down I am so pretentious. I am only just twenty-one and really know nothing at all about life, let alone the entire history of literature, or the oeuvre of Borges. But at the same time, it feels as if all the knowledge of the world is inside me when I read, as if I myself were the Library of Babel. I used to absolutely want to be a writer. With ten sheets of paper, an old fountain pen and a beautiful view, I considered myself fully prepared for an existence as a writer. Only a romantic attic room was missing.

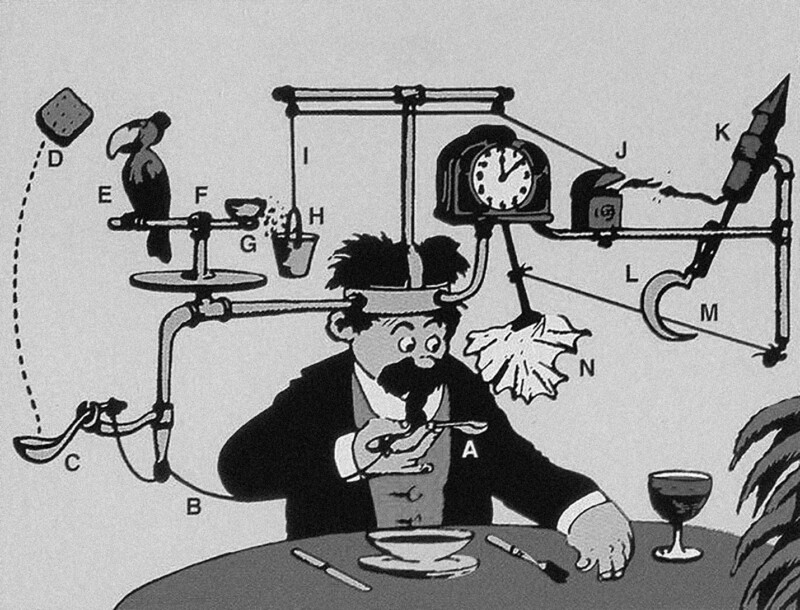

But alas: after hours digging into the deepest recesses of my brain and countless minutes staring at those sheets of paper, there were about twenty sentences on my sheet of paper (it became a very short story about a medieval damsel with a horse and she fell in love). Perhaps that was the moment when I should have realized that I don't have to search my own imagination for words, but might as well use those of others for inspiration. There are so many works of art and texts to work with. Dadaism made this its own, and these techniques are also widely used in pop art. There is an almost inexhaustible source of newspapers, posters, books, photographs, drawings, paintings and so on to create new things with.

In his essay Heaven and Hell, writer Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) talks about a difference in perception and experience of bright colors in modern times versus the times of the Ancient Greeks or the Middle Ages. Bright colors were scarce then and reserved for the very rich. Even kings, princes, emperors and other distinguished figures often knew only a small part of what colors there were. Ordinary citizens saw only brown, gray or green colors in their homes and clothing, making the effect once so great when entering the church where an incredible spectrum of colors in the stained glass windows filled the entire room and spread across paintings detailing bright red or lapis lazuli blue. Today, bright colors are visible everywhere and we are overwhelmed by them, so to speak, reducing the impressive effect. There are colors on every street corner, in every town or village, in every store; you can hardly ignore them. Huxley himself writes it in these beautiful words:

"Bright pure colors are of the essence, not of beauty in general, but only of a special kind of beauty, the visionary. Gothic churches and Greek temples, the statues of the thirteenth century after Christ and of the fifth century before Christ - all were brilliantly colored. For the Greeks and the men of the Middle Ages, this art of the merry-go-round and the wax work show was evidently transporting. To us it seems deplorable. We prefer our Praxiteleses plain, our marble and our limestone au naturel. Why should our modern taste be so different, in this respect, from that of our ancestors? The reason, I presume, is that we have become too familiar with bright pure pigments to be greatly moved by them. We admire them, of course, when we see them in some grand or subtle composition; but in themselves and as such, they leave us untransported.”1

I compare it to language: it is so present in our lives that there is no escape. In the period before the invention of printing, or even further back in time: before writing existed, people were probably less exposed to language. Or at least in a different way. What would the world be like today without any form of language? How would we communicate, learn or pass on new things in this day and age? Perhaps it is an experiment worth trying: living without language. No reading texts, no speaking, no singing or shouting or thinking. Is it at all possible to live in a world without language? Can you survive then? Perhaps we would hardly notice, should all language around us suddenly disappear. All words would then be gradually replaced by images, and nothing would remain that contains a letter, a word or a sentence. I find it hard to imagine, but of course this could be due to my own incredible fixation on everything to do with language. But I know I am not the only one who feels this way; Jan Blommaert also admitted in an interview in De Standaard (2020) that it is frightening to lose your voice, that it “eats away at your humanity”. To this he added the beautiful words ‘the ability to express yourself in language makes us human’. Every person has some form of language in them: spoken, written, sung, played, thought…

But then I wonder: why is it that some people are more language-sensitive, just that tad more attracted to words than others? As an illustrator, why do I make poems and not drawings? Why do I not paint but write? Do I have to justify myself at all for what I create?2

French poet Charles Baudelaire approached the city as a text - street names, placards, posters and monuments. In his poem Le Soleil from the collection Les fleurs du mal, he stumbles over words like cobblestones, describing the city:

“Le long du vieux faubourg, où pendent aux masures

Les persiennes, abri des secretes luxures,

Quand le soleil cruel frappe à traits redoubles

Sur la ville et les champs, sur les toits et les blés,

Je vais m'exercer seul à ma fantasque escrime,

Flairant dans tous les coins les hasards de la rime,

Trébuchant sur les mots comme sur les pavés

Heurtant parfois des vers depuis longtemps rêvés.”

I look at language as a form of architecture: words are building blocks to write with. And those building blocks are no one's property; everyone can and may use them as they wish. We all speak with the same letters, sounds, words, sentence constructions and so on. We are constantly complementing each other or repeating what someone else is saying. Language can be a form of abstract art, as in the sound poems of Hugo Ball. He wrote phonetic poetry with abstract sound units. The phonemes have no meaning, so the focus shifts to the musicality of the voice and the sounds produced. At the same time, any form of writing, poetry or prose, is a similar collage of words and sounds that everyone uses. Only in some the meaning is already pushed forward a bit more than in others. Carefully I try to extend this to visual work, but working with images in the same way is often met with incomprehension. I quickly end up on the street of ‘plagiarism’. After all, every painting, photograph, sculpture, drawing, logo or other picture was made by someone, they are works of art with an owner. If I write a sentence, does it belong to me? Do I own this text? And using texts or images just like that, is that still allowed without mentioning the original creator? Conceptual artist Richard Prince did it and became world famous. In 1989 he took pictures of advertising images from magazines and presented them as his works of art in an exhibition. The most famous photo in this series was originally taken by Jim Braddy for a Marlboro campaign. Prince himself says about this that his goal was not to steal, sell or claim a photograph taken by someone else. The work is about claiming, about photographing something that had already been photographed before, and about the identity of America in the 1980s. It's a simple concept: Prince uses material he has found. And yet it is met with enormous resistance, because appropriation is not appreciated by everyone. In addition to "stealing" their work, what also went down the wrong way with the original Marlboro advertising photographers is the fact that it was not at all important to Richard Prince who had taken the original photograph. He himself said the following in an interview, “It just wasn't important who took the photograph. I took the photograph. I literally took it.”3

Prince saw advertising images as public domain. The idea of “re-photographing” and authorship was challenged by his work. He tested the limits of what is acceptable within the law around copyright, elevating the images to art in a similar way that Andy Warhol did with his Campbell's Soup cans and Marcel Duchamp did with an upside-down urinal. Sherry Levine did the same with Walker Evans' photographs in 1981, but named the series After Walker Evans after its original creator. Richard Prince descends from this tradition of contemporary art. And basically, art is nothing more than the continuation of previous traditions and ideas. One of the oldest and best known definitions of art is mimesis, the imitation of the environment. This is also immediately the definition that a large portion of artists, critics and audiences agree with, besides art as an expression of expression. But artists mostly imitate each other and themselves, which is not a new fact. According to Warhol, an artist's job was not to create new images, but to reproduce what society had already accepted as beauty. And then, of course, there is Picasso's famous statement, “Good artists borrow, great artists steal.”

And, “the best artists” turn it into something else or provide a finishing touch, like Marcel Duchamp who drew a mustache and goatee on the Mona Lisa and named her L.H.O.O.Q. ("Elle a chaud au cul"). And so it became a "tableau dada. Here the artist deliberately did only a slight modification so that the original work was still recognizable. The intention in this case is not to appropriate the work, because pretty much the whole world knows that Leonardo Da Vinci is the original painter of this work. But just that small adaptation contains humor. The Mona Lisa has been appropriated several times: The Simpsons turned it into Mona Lisa Simpson, Svetlana Petrova placed her cat on Mona Lisa's lap. Warhol also made one with 30 images of the iconic painting in 1963, titled Thirty Is Better Than One. That same year, he also made Colored Mona Lisa, a collage of the portrait in different colors. American painter Jasper Johns drew inspiration from this to create Seasons, where he appropriated the Mona Lisa in a tribute to Warhol and Duchamp.

NOTES

- Aldous Huxley, Heaven and Hell (1956)

- Dit zijn retorische vragen, uiteraard

- Richard Prince in een interview met 100 Photos Time

Text: Régis Dragonetti.