Handel's Serse

Admittedly

A new spring, a new opera production by the Conservatory. This year's programme includes Georg Friedrich Handel's tragicomic Serse (1738). Florian Heyerick is the musical director, Benoît De Leersnyder will direct. Onrust spoke to both teachers. There was room for roguish smiles, but a more serious wrinkle also occasionally cleaved their foreheads. We tackle them in that order. Komitragic, quoi.

Admittedly

Admittedly, the choice of Serse is in some ways a practical one. Every year, the singing teachers look for a work that suits the voices available. After last year's Stravinsky double bill, it was time again for baroque. The fact that castrati were often used in the past has its advantages today, by the way. With a wealth of sopranos in the singing class, it is certainly convenient that the male leads are also written for high voices. For the role of Serse, master students Nele De Soete and Esther Verheye are the perfect people.

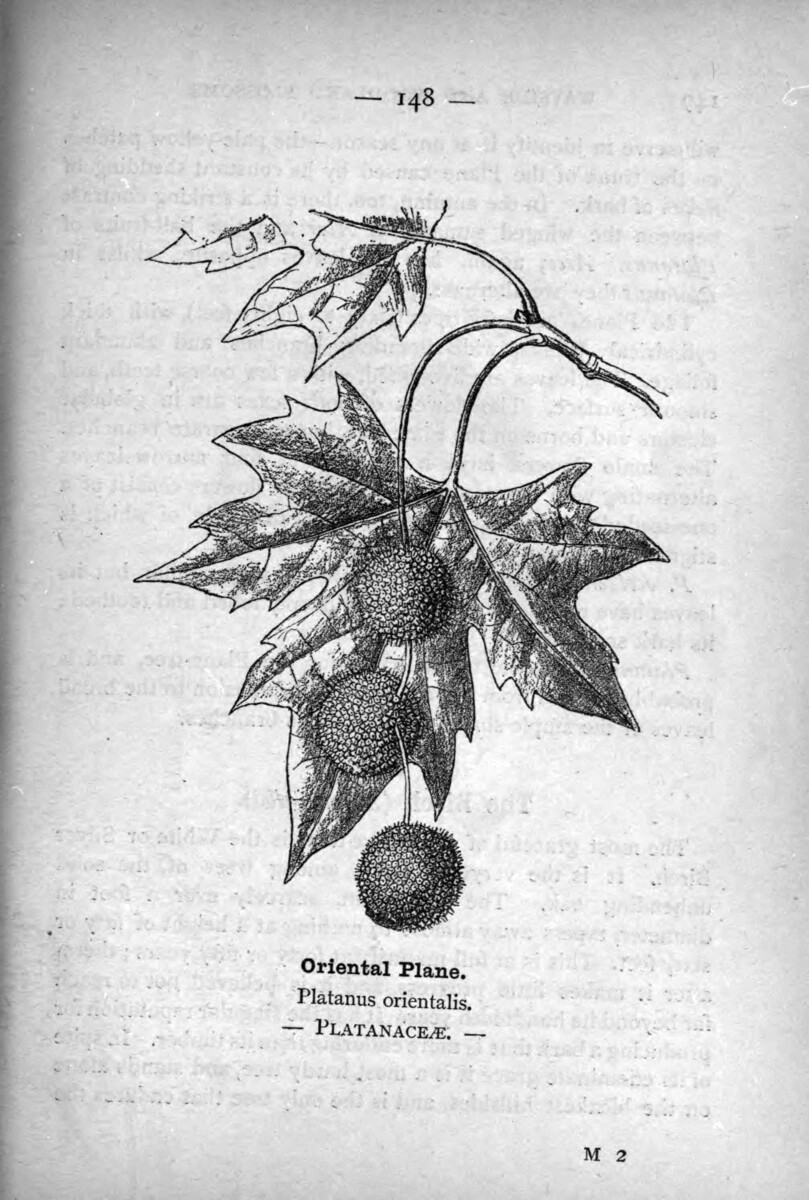

Admittedly, that main character is the stereotype of the exotic tyrant. Serse, son of Darius the Great, is king of the mighty Persian empire and quite nuts. When the Hellespont thwarts his war plans, he punishes the turbulent waters with lashes. A beautiful, shady tree, on the other hand, is rewarded with a royal ode.

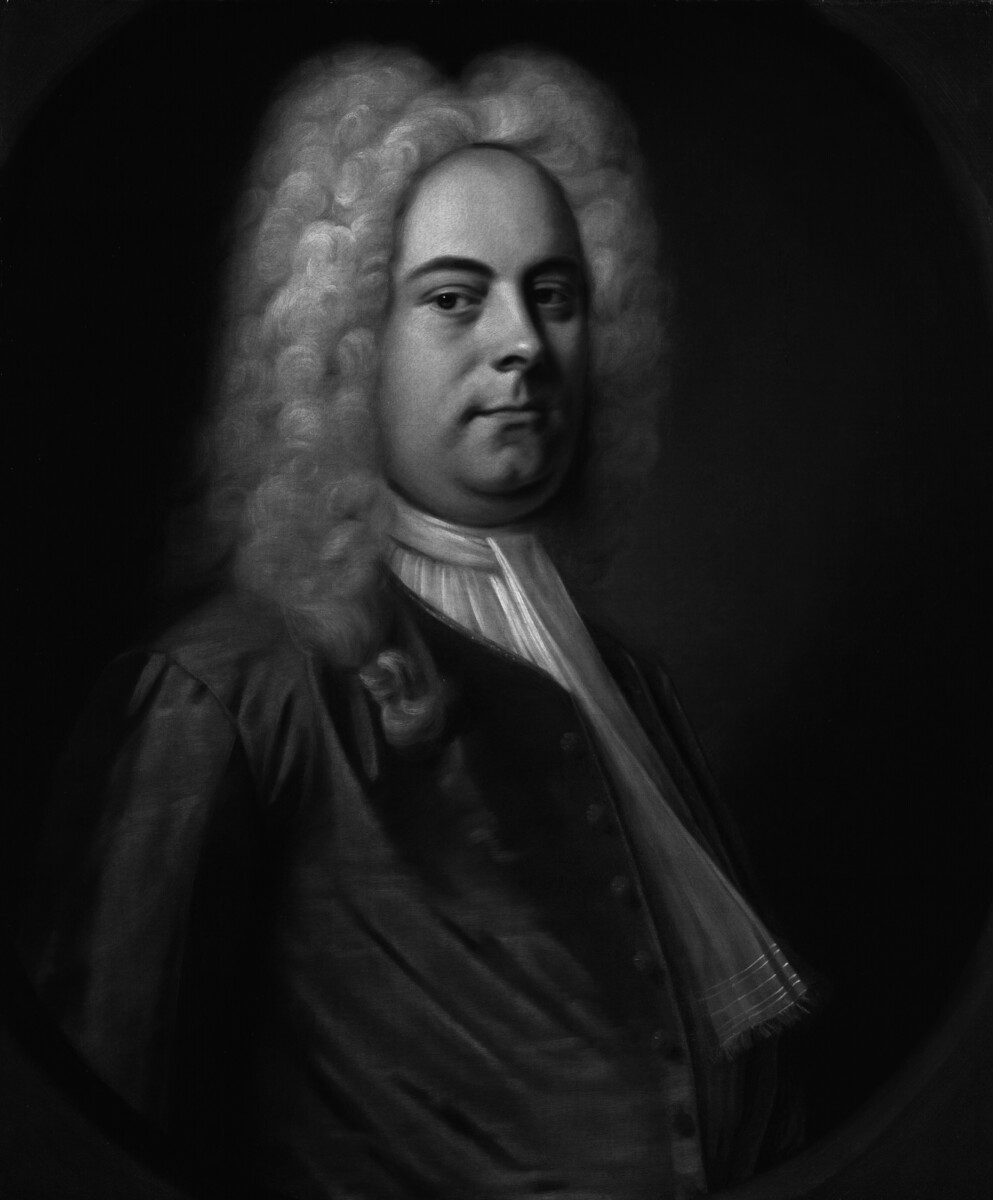

Admittedly, we know this lack of ontological distinction in our parts too: a petulant Jesus withers a fig tree in the Marcus Gospel, and Suetonius tells of Caligula wanting to make his favourite horse consul. By the way, don't you think Handel in his portrait looks a bit like the Antwerp mayor before his slimming cure? Wig admittedly not included. Power, it does something to a person.

Admittedly, Handel was probably a bit overconfident himself with Serse. With barely seven performances, it was far from his greatest success. As an acclaimed composer, Handel had formed his own company. However, the competition in London in the 1730s could be described as an operatic civil war. As the rival company played the public with fashionable works of lighter quality, the Italian opera seria was somewhat on its last legs. Handel, however, believed that the genre just needed another blockbuster of his. In vain, not much later he would devote himself only to English-language oratorios.

Admittedly, that label 'seria' need not always be taken literally. The narrative is rather thin and contains quite a bit of blandness, at least by bourgeois-romantic standards. Handel's Serse was indeed meant as entertainment, high-class entertainment for well-to-do people. De Leersnyder summarises the libretto as the fortunes of 'four adolescents and two dummies'. Indeed, the web of interrelationships between them seems plucked straight from the playground: Amastre likes Serse, Serse likes Romilda, Romilda likes Arsamene, her sister unfortunately too, yet Arsamene only likes Romilda. And you'll never guess: there will be troubl.

Nevertheless

Nevertheless, Handel had a twistedly happy pen. 'A hit machine' Heyerick calls him. The man came up withe the most charming melodies effortlessly. Elaboration is sometimes hard to find and bass lines tend to bob along. The composer's tight work schedule undoubtedly had a lot to do with this. The London audience had to be entertained, so there was not always time to polish everything to perfection.

Nevertheless, Handel was endowed with a particularly broad palette on a dramatic level. The music lifts the libretto above itself. So Serse is by no means a vaudeville. For instance, the first note of the first recitative is 'Frond' from 'Frondi tenere e belle del mio platano amato' (Tender and beautiful leaves of my beloved plane tree). A character drawing on a microscopic scale it is, in the sense that the monarch seems to falter from the start. De Leersnyder certainly sees scenic potential in it.

Nevertheless, the director has not been shy about cutting an hour out of the opera. Not to worry, that pragmatism could surprisingly be called an authentic performance practice. In the eighteenth century, people did not shy away from this kind of intervention. One aria more or less, possibly even by a different composer, some cuts in the instruments at the last minute because the orchestra pit was a bit small... They had to cut their coat according to their cloth.

Nevertheless, there is a poetic concept behind the cuts. De Leersnyder based himself purely on the dramatic course, without taking the music into account. He is convinced that the future of opera lies in this direction. Today, music and staging are considered too separate. Sometimes opera houses work with a choreographer, sometimes with a visual artist, who then just 'does his thing with it'. De Leersnyder himself, by the way, does not like baroque sets. An empty stage is his trademark. However tender and beautiful the leaves of the plane tree, they will not be seen. Not without imagination at least.

Text: Régis Dragonetti.

Serse by Georg Friedrich Handel

Serse: Esther Verheye & Nele De Soete

Arsemene: Kaylee Galle

Amastre: Anna Nuytten

Romilda: Louise Guenter & Mieke Dhondt

Atalanta: Liza Dedapper & Franches Dhondt

Ariodate: Valery Alexeev & Tom Van Bogaert

Elviro: Andreas Vromant & Arne Gunst