Ghent – Carrara – Ghent

For over ten years, the sculpture class has made a yearly trip to Carrara. They visit the world-renowned marble quarries, as well as studios and other places of interest. An exhibition that sheds light on this tradition will take place in the Zwarte Zaal in November. Below, teacher and inspiration Isidoor Goddeeris muses about his love of marble.

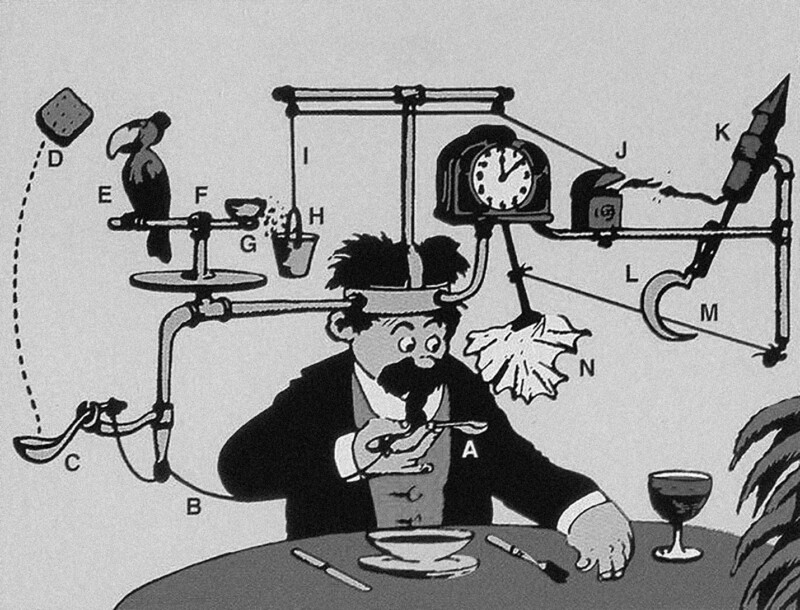

Teacher of photography Willem Vermoere and Paul Demets tell the story of a stone and a photograph. Finally, Simon Masschelein tells us about an 'artificial wonder of the world'.

Telomeer (Tellaro)

Duik op. Leg een steen aan de voeten

van een man. Leg hem voor, maar gun hem

geen vuile blik. Laat de materie verteren.

Hij vergeet het water en opent zijn

geslotenheid. Ruik je de zee? Hij spant

zijn witte spieren. Zo glad. Uit zijn hardheid

vloeit vlees. Nu hij uit het water

verdwenen is, draait de vis rondjes

rond het weggenomene, mist zijn paaiplek.

De vooravond leest onverschillig verder,

bladert in de achtergebleven krant. Hij wordt

marmer en graaft zijn voeten in het woordzand.

Ode aan weerbarstigheid

At a young age, I took a thorough training in stone carving and sculpture at Monument Vandekerckhove, a restoration company specializing in historic preservation. The fire and love for the trade of my teacher and colleague Roger Gadeyne turned out to be very contagious. From him I learned the details and finesse of the craft. Later I went to Italy on my own in search of more knowledge about working and sculpting in marble. Where better to go than Carrara, the marble Mecca. I worked there in historic studios like Laboratori artistici Nicoli, where big names from Henry Moor to Louise Bourgeois and even our "friend" Jan Fabre commissioned work. It's hard not to fall in love with Italy: the beautiful landscape, the sublime marble, the sympathetic locals, la Cucina Italiana. For years I returned there, so by now I speak the language.

But why work with marble at all? There are a hundred reasons not to! First of all, it is incredibly hard work: grinding, polishing, sanding,… Noise and dust are permanent studio companions. Not to mention the equipment. With such weights, you often need a forklift truck or other appropriate transportation, and exhibiting also requires quite a bit of manpower. A studio with outdoor space is essential. Furthermore, marble is quite an expensive material to work with and difficult to get your hands on in Belgium. But for all the unruliness, I love it! It is a wonderful material, of which there are thousands of varieties and colors. Its extraordinary appearance pulls you in and makes you want to touch it immediately. Not only me. For centuries it has been caressed and worked on by the most famous sculptors. Even in contemporary art it is once more a highly prized material: Michelangelo Pistoletto, Giuseppe Penone, Mike McCarthy. Part of the admiration, I think, comes from its laborious processing. Working with marble is a pleasant struggle. I like to share that feeling with interested students. A true work of love.

Buco della luna

Buco della luna

A place, an artificial wonder of the world that, hidden behind its hair, sits perched toward the village. It follows the trucks of the stone industry. Feels the marble dust descend daily from the higher neighbor. Hears the stone rolls from the quarry as an occasional snore. A true character, some god. But if you look very closely, you see a soul through the slit of his eye. He appears, only for a moment, and it makes you wonder what it would be like to talk to it.

An old disused concrete building, built as a cement factory in the 1950s and the gateway to the quarry where this cement was mined. Built on a steep slope. The armament was as externally as internally present in the concrete, attesting to its many and rough years of life. Its pillars like stable graceful feet, bearing its triangular head playfully. Staring, like someone in love, with selfaware, solid confidence. Leaning on the palm of her ‘hand’, with a slight nonchalance in her ‘fingers’, visible by a slight bend. Supported by elbows or knees that are split, full of fissures from the pressure that has been applied to them for so long. Cracked concrete with the occasional window, through which you can see that massive blocks of marble, purely by their weight, quietly bring down the building. Cement cones hanging from the bottom like stalactites.

People call this place "Buco della luna": "the hole of the moon.

A forest path right after a sign that said ‘MOONTEK’ took you to the side of the factory, where you immediately discovered it covered by graffiti. A staircase through the monument, as if you found yourself in a scene from a Lord of the Rings movie, in which your character took a trip through the mines of Moria, led you windingly back to the forest on the steep slope. A little higher up, a hole in the rock wall. A tunnel. As you step into it, you can't make much sense of the space in front of you, and the wall keeps rising in height, until you finally put your first foot out of the tunnel, and see the sky.

'Buco della luna' is an old cement quarry, where man dug too deep, causing the top to fall out, resulting in a hollow mountain with a hole in its top. This creates opportunities for the sun but also for the moon to shed light against the rock walls, which still show slight traces of cutting. The walls push inward, insulating you from wind and sound. You might hear some forlorn wind whistling, birds afar, singing. A squeaking bat or some insects buzzing. Yet everything seems more subdued in there, as if you have ear plugs in or have dived too deep or flown too high without experiencing pain or discomfort or anything in your ears. Because of the size of the bottom surface it is impossible to estimate how high the walls tower above you. Start walking, and you get the idea that space is an illusion and you are stretching it as you step. Only when you climb one side of the wall, and then look down at a fellow visitor opposite the wall in front of you, do you get a clearer idea of where and how you fit in this place.

A place, an artificial wonder of the world that, hidden behind its hair, sits perched toward the village.

The sides of the walls consist of low walls of concrete, but inside grow trees and bushes, giving the feeling of an oasis in a hollow mountain. In the middle is a circle of stones built around a cairn of stones, with red letters on it. They reminded me of the sculptural scarecrow-like signposts in Norway. Stone stacks with a red T written on them. You always became happy when you saw these cairns looming on the horizon. The only method, combined with a compass, to maintain a certain structure in this landscape.

This feels as some kind of leftover creation for some ritual by a cult. But too artificial and nearly wasted, in a way that people would consider empty as to possess any kind of spiritual value.

People call this place “Buco della luna”: “the hole of the moon”. When the moon shines directly into the hole, its light reflects on the remaining white tones of the marble walls. The sun could do this too, but a reflection of moonlight on marble works better because everything else is dark. You get a searing white-hot landscape. Like a molten silver metal.