Hannah De Bie, Erin De Schepper, Hans Druart, Luc Deschepper

Mountain and school speak

How to move beyond the flat plane more often? - Hannah De Bie

Nothing here is mine and yet I am involved in everything. - Wim Cuyvers

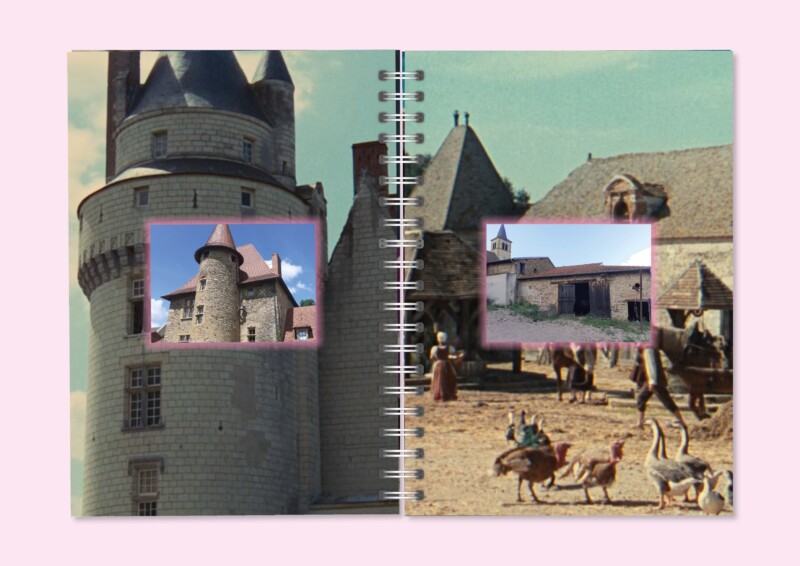

Landscape and garden architecture students Hannah De Bie and Erin De Schepper concluded their studies at the Bijloke with a week-long study trip to a remote mountainside in the Jura. Since 2022, the department has organized the annual "Montavoies" workshop, named after the mountain on the edge of the French Jura, where Wim Cuyvers bought a large plot of land in 2005. He transformed it into Montavoix —or, as its ancient paths suggest, a "Mountain of Voices,"— where the landscape speaks through its history. Since then, Cuyvers has been working on his refuge, a hideaway for people in need. An architect-artist, storyteller-speleologist, and forester-guardian, Cuyvers is always on site, tending to both the land and the people who find their way to him. Whoever comes, works alongside him.

What has this mountain offered to the students, and how might it also enhance their view of the Bijloke? What do these two landscapes share—or not—and what can we learn from them? This exercise in moving between a mountain and an urban art school space sparked meaningful discussions. What is it now, and what could it become? Just before their graduation, we found these questions driving a conversation. Their teachers Luc Deschepper and Hans Druart and editor Liene Aerts joined them at the table. A conversation becomes a brainstorm.

We start at the top of the mountain

LIENE AERTS

What does a day at Montavoix look like? What does Wim do, what do you guys do?

HANNAH DE BIE

We restore the landscape, think about what restoration is. I think that's where the biggest connection to our profession lies. It is enriching to be able to walk around in the same, relatively small place for a week, with 15 other students and two teachers, on the flank of a mountain.

ERIN DE SCHEPPER

And therefore being able to focus on 'being there', observing, listening to the place and what Wim has to say about it.

HANNAH

Normally you walk past a landscape, but now you stay there with someone who has known that place for so long, pointing out historical elements and old patterns to us. For example, these are the logical lines that people used to follow from the refuge (formerly a farm) to the village and we can restore them. Observing a landscape, and doing so in detail, is something I definitely take with me.

HANS DRUART

Wim is an incredible storyteller. He raises the right questions, makes you think. Everything goes at ease which also allows time and space to think. In the refuge, there is no electricity, no running water, no wifi. It is all basic. There is nothing super concrete, except the fact that you are there with Wim and the others working on something. It seemed like an interesting place for our students, because what do you do there: work, with your hands and feet in the earth. Wim takes you from micro to macro level: he uses maps to explain the site, but also walks it. You walk down the ridge to learn how the landscape, with crests and valleys, is put together. You walk down the open corridor under the power line, from mountain to mountain, as the animals instinctively do. He manages, receives, cooks and gives direction without direction. He calls himself the gardien or the forestier, depending on which role he is taking at the time. Even before he bought the site, he was strongly concerned as an architect with the question: what is public space? How do you make it accessible to everyone? These questions are central, in short, together with Wim you can theorize about this for days.

LIENE

You talk about "listening to", "working there" or "we put ourselves to work", could you go into more detail on this?

ERIN

The first day we took a walk around the entire site to explore it, along the borders and inside, to see what was already there and what could still be done. The following day, we created meadows. Wim walked ahead of us with a brush cutter, through the wasteland and rough terrain, uprooting trees here and there. We picked up everything and collected it in bundles of branches on the side. He wants to clear certain stretches of forest, after which horses can maintain it by grazing. Indeed, forest and bush shoot up very quickly. Another group tried to dig out a horizontal path from a steep mountainside, building it by tamping earth. Yet another group cleared paths already winding along that same mountain flank. These paths tend to flatten out again and again, so you must dig them out, against the mountain. A mountain always wants to slope and grow back. Going against this as a human being requires constant work.

HANNAH

With Wim, there is never a beginning or an end. You tap into the work of your predecessor.

HANS

On a plan, you quickly draw a line of where a path should be. Until you're on that flank itself and then you feel, "that's not going to work." Then you have to start looking at exactly where you want to go, how fast you descend, how you connect down below. This only gives real insight into a landscape, a landscape with relief and drainage. Things you have to feel, see and that don't just read themselves off a map. Which makes it valuable.

ERIN

This goes down to the level of trees serving as steps. Only by trying a few sizes will you start to feel what works best.

Een opstap naar de Bijloke

LIENE

You speak of "making meadows in the advancing forest as the goal" which reminds me of how 'good' we are at shaping landscapes to our liking. Whereas the Jura is half forested, rugged and vast, the Bijloke is a comprehensively flat and managed, water-locked and enclosed area. From the 13th century, the Bijloke, then a collection of marshy meadows or marshes, was a site for healthcare. From the 1980s, it took a new direction, from care site to art site. The Pauli hospital became an art academy (KASK), the oldest infirmary became a concert hall (Bijloke Music Centre), the abbey became a city museum (STAM), the abbess's house, followed by a maternity ward, became a library (Kunstenbibliotheek),... After seven slow centuries, the site thus acquired a whole new skyline with totally different interpretations and users in just forty years. In recent years, I can clearly sense a new kind of wind acting on this 'ridge'. There is now less mowing and pruning and more looking and scanning. Or viewed from my experience with exhibition projects, from: students dig wells and make mountains, in nature, but not in dialogue, over 'the head' of the ground. To: engaging in conversation when these proposals come up, trying to reason from the perspective of 'the skin' of the earth. With, as a result, often a different, less invasive approach to the soil. This is why TASK was set up, an initiative of the infrastructure service and the landscape and garden architecture department. Luc, you are a key figure in TASK, how would you describe the "purpose" of our current garden policy?

LUC DESCHEPPER

Then I look at Montavoix. Wim is vigilant and asks the question: how do we keep the balance? We as humans walk around the earth here, constantly filling it in, and nature's possibilities for development and recovery are limping behind. We certainly don't need to go back 2,000 years, but it is still about putting some distance between ourselves and things we have taken in. This is also how we try to approach our campus gardens: first we look at what comes naturally and only then do we look at to what extent, if any, we can respond to it to promote development. Some of our gardens used to be hayfields and the last couple of years these have been returned to their original state by organizing scythe days for the students. Given the positive evolution and enthusiasm with which these initiatives are received, we want to set up more outdoor activities in the coming years. For this, I look again to Wim's approach: efficient planning and organisation is not part of his practice, but he always has a direction in mind, following nature's slow development time.

Binden met de Bijloke

LIENE

Our site has more square metres of indoor than outdoor space. The gardens are the public 'heart' of the campus, yet, with one exception, they bear no names. We decide that they deserve more attention and draw up an action plan... Here again that difficult search for balance: how do we make things happen without too much fixed structure while here we are with a school and programme focused on planned thinking?

LUC

This is something many people want: certainty about the future, being able to work towards a so-called final or target image. You don't know what or where it will develop, but you do know, and this is the crucial thing: it WILL develop, because you leave it to nature, it will be fine. Once the well is dug, and provided you stay away from it, you also create new development opportunities for nature, with a wet situation below and a dry one above, or a warm dry south side that insects love. It is the structured, results-oriented, human thinking that we need to unload. It's a tricky contradiction with how we are trained: you draw a picture and then strive to make it real. Whereas they are two worlds.

LIENE

I have found this kind of insight to be a very interesting awareness process over the past few years. Could students also work more on specific practical case studies exactly from this insight? Inspiration, perception and empathy alongside organization. Or how do you see this as graduating students after spending three years here? How do you experience this place?

HANNAH

When you arrive here, it doesn't feel like a school, more like a place of inspiration surrounded by greenery. Over the years and classes, there was a growing realization that there was too much gardening. Just think of the way some trees were pruned incorrectly or too much. You are given examples like "look at that tree, shrub and grass over there, look at how it is developing" before your eyes. The programme definitely belongs here.

LIENE

So what do those lessons look like, do you take walks where you stop at the small and big things?

ERIN

Besides pointing out plants, we were also taught techniques. In the first year, I once had to measure one of the apple trees, because I was told that I had drawn this kind of tree much too small on plan.

HANNAH

With a massive, extendable ruler! You arrive here in your first year and you have no sense of scale. You often draw the trees on plan too small with a diameter of 2 to 3 metres. You don't consider how big a tree grows in comparison to a building, for example. Then in the first year, in one of the first lessons, we went and measured the trees here with one of those very large extendable rulers. Turns out those are 15 metres and taller!

LIENE

Like what you said earlier about looking at the plans in the Jura region and how different it is to be on the ground. From the experience, we can then refer back to the flat plane.

HANNAH

I think it would be valuable to extend this into the programme, to explicitly step away from the flat plane from time to time, in the project weeks for example.

LUC

Partly as a result of this conversation that I am very interested in, it does appeal to me to readjust the approach towards the new academic year. You can restart every year. We make sure the theory lessons start with reality. You have to learn reality first, then get to know yourself. Who am I as a designer and only then can you start making things.

LIENE

Maybe we should invite Wim to the Bijloke sometime? Start one of your walks every year with an additional, personal perspective on our place of work and study. Do you guys have any ideas?

LUC

Another example of giving space back to nature are the spacious, circular fences under the trees in our gardens. These prevent access. It initiates a change. It is an invitation to look at the greenery surrounding us with a different perspective. What is beautiful, neat and clean? And then what is not beautiful? For instance, I recently noticed something in the glass corridor (glazen gang): on the side of the KASKcafé terrace we no longer mow, which when viewed from the inside gave a 'beautiful' image, but from the outside I found this less beautiful. It reminded me of a framed work. Remove the glass and you have something else. Nature as a picture. I'm going to do something with the students on this as an exercise at the start of the year. Search for the beauty in, say, a nettle. Just think of its ecological value, and yet we destroy it.

HANNAH

This is also a psychological fact. In the book The second guide to nature-inclusive design, biologist and landscape architect Maike van Stiphout writes about how to convince people to leave the weeds, side weeds rather, and thus achieve a biodiverse environment. If you just let it grow, people see something ugly and dirty. But by mowing a subtle edge around a patch of flowery grassland, you do indicate that it is being looked at. "It's not left behind so it's ok." Apparently, something is only allowed to go wild from the moment a frame is drawn around it.

LUC

It becomes acceptable, maybe because they see a connection with another human being in this?

HANS

And also engagement, people become aware of what their own role is.

Een wild Bijloke

LIENE

That which is feral and abandoned brings us back to Wim. According to him, public space should be able to be a place to hide.1 Is there room for this kind of wilderness at the Bijloke?

HANNAH

Wim pays attention to places that are not generally accepted, turned their backs on. For instance, with students he went to places next to the highway where prostitutes and drugs can be found. He asks not to completely eliminate these kinds of marginal spaces while designing. So how can we look at the Bijloke from this perspective?

ERIN

I think the Bijloke is private but equally open. I think this does fit in with his theory of a publicly accessible place. People also hang out here in the evening and at night. Things happen that cannot happen in other places in the city. It has a lot of interesting nooks and crannies.

LIENE

Since the pandemic, the site has increasingly become a hangout: damaged artworks, rave parties on the esplanade or a homeless person seeking shelter here. The Bijloke’s night side has a smell that lingers. You can discover it on Monday mornings in the open gallery next to the entrance of the Kunstenbibliotheek. If you open the door, you'll step right into the sticky traces of the weekend.

HANS

Interesting, there is a need for places like this within a city. By the sounds of it, the Bijloke offers the chance to find such places. So do you want to keep that or not? From the moment you start stimulating it, you're interacting and then again that's not necessary, but the potential is there and that's just what makes it fascinating. What is a hangout? Is it young people coming here with cans of beer, is it about drug use? I would find it interesting to map this out at some point. It reminds me of Wim's story of the graffiti. Youngsters on Montavoix found an overhanging rock on which they did graffiti. Vandalism according to the neighbours, a contemporary form of rock drawing according to Wim. He sees a kind of primal occupation in it. It is about man looking for opportunities to do his thing hidden away, whether it is graffiti on a rock, vandalism or a sticky pair of shoes.

1 Cuyvers wrote a unique, ever-expanding and eye-opening definition of public space on his website.

Text: Liene Aerts