underneath it flickers

Film student lau persijn engaged in a dialogue with nature, and nature responded through image and sound. underneath It Flickers, lau’s master’s thesis, is both a search and an encounter, a conversation and a deep listening experience. It is magical yet strongly connected to technology, representing a profound intuitive investigation and a direct testament to a place. It’s much more, but you’ll need to watch it to fully understand.

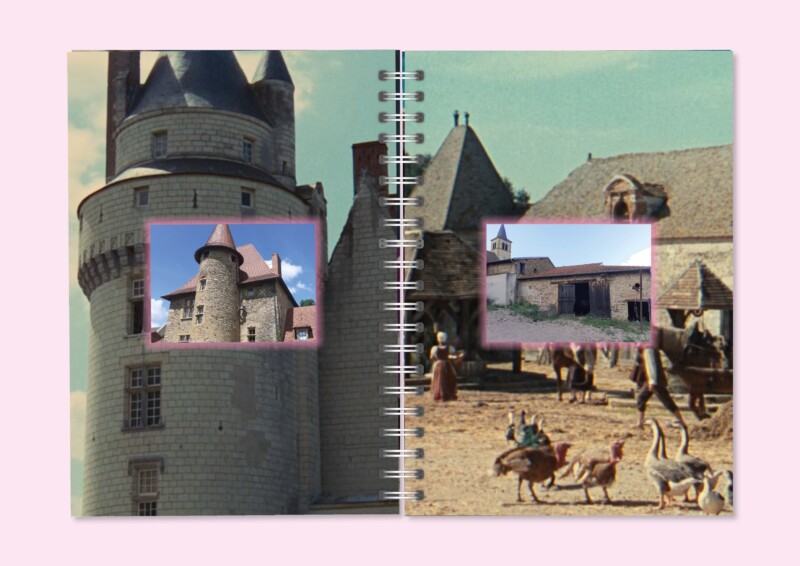

The film began with La Friche, a 25-hectare wasteland long owned by the SNCB. They had planned to build a large marshalling yard there. It was later sold back to the city of Brussels, and there are occasional plans to develop it or not, depending on the political climate. Meanwhile, nature has taken over the space. Brussels often views La Friche as empty, but it is a vibrant place with significant biodiversity. The city needs such spaces. I was looking for a defined place where man and nature have an alienating relationship with each other; a tension of mutual care. The ongoing search for how man and nature coexist – that was my focus. We began by observing; the evolution in the film mirrors the process of making the film. Initially, it was about getting to know the place, watching and listening attentively, and not intervening too much.

Laurent Derycke

When did you visit for the first time?

I knew people involved in a gardening project there. They gave me the access code, since it’s all fenced off, with only one gate on the street side locked. Surrounded by houses, you can’t see what’s inside. Suddenly, you’re in 25 acres of nature with a single railroad running through it. From that initial fascination – “Wow, this place exists and nothing actually happens to it” – I started visiting regularly, eventually bringing my camera. It’s all filmed on analog film, with the same camera and zoom, always from the same concrete perspectives. I wondered, “What if we reflect on that and start putting these things on screen to show how we look and listen?” Also, “What if we used different perspectives? What would emerge from that?” I started exploring sound and ended up using a geophone, originally designed to measure earthquakes. The device picks up the very lowest frequencies in the earth’s strata. I placed it in the ground to see how the passing train would affect it and what impression it would leave on that piece of land. The entire earth trembles. Then I also used a hydrophone.

LD

And from acquaintance to conversation?

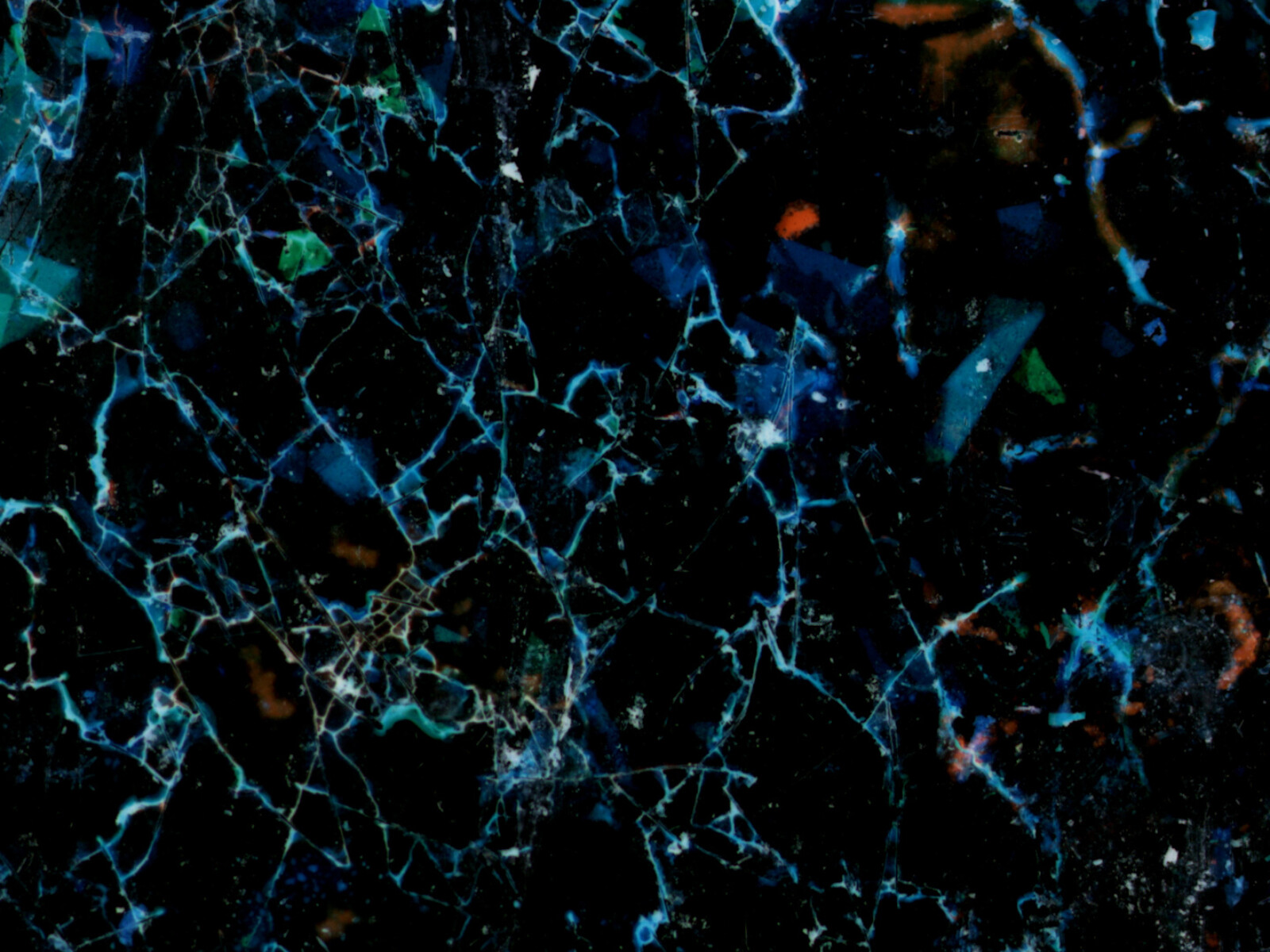

At first, it’s “I want to get to know you, but I’m hesitant to do too much,” and later it becomes “We will work together.” The filmstrip that I placed in the water and buried in the ground, which I later retrieved, represents the most concrete form of that conversation. “I film you, and I want to give that to you, so you can do something with it.” Surprising images resulted. There are three sequences. The first two contained recognizable images. I left them in the water for three weeks. The final sequence remained for two months. While it still includes some recognizable images, the rest became entirely abstract and colorful. The film was left in the ground and water, and La Friche influenced it. It was about filming and then reflecting on what we had captured. “What does that say about the place? What does that say about us?” There were often one, two, or three weeks between filming sessions. This was beneficial – not having a continuous shooting period allowed for reflection. “How do we look, how do we listen?” This also allowed us to incorporate all the seasons and observe the place in constant change.

LD

It also reflects your story and process. Analytical and charming at the same time due to the journey you present. Then there’s the technical layer, all the equipment you use. It’s a fascinating hybrid of many elements.

We were able to be playful in that way. We experimented with many things and discarded what didn’t work. We filmed one day creating a large cyanotype, making literal prints of branches, leaves, and grasses... It was beautiful but made the film too dense. We found that the prints on the filmstrip were much stronger than the cyanotype.

LD

How much material did you end up with?

About an hour in total, including the filmstrips buried in the ground. I have more material in the sound than in the images. Filming on film is very expensive! With film, you quickly become aware of whether you really want to capture something. There are a few shots that I think should have been a little longer. There’s one shot of a bramble where a plane comes into view. I could tell it was about to stop, as a Bolex shot is a maximum of 25 seconds. But at the same time, I liked that the instrument decided when it was done for me.

LD

If I’m correct, there is no camera movement at all?

That’s mostly a personal preference. It allows me to focus on something longer. Attentive viewing is a constant in the film. For the sound, I went there several days with different microphones to make field recordings and be surprised by what I heard.

LD

What impact did that place have on you?

I felt connected to that place. It felt like a refuge where other beings could escape the city. The idea that the place could disappear also affected me deeply. I believe that certain parts should be protected and inaccessible, but people should get to know the place. There’s a path in the middle where people can walk. If more people visited, they would also connect with that place.

LD

You work at the intersection of documentary and fiction. With the captions between the pieces, you build a larger narrative about the place, the animals, and what’s there. You achieve a lot within the duration of your film.

I also wanted to show the richness of that place in many ways, but without being too bombastic.

LD

But you maintain that line very pure. You cultivate curiosity and effectively convey your fascination. You show the fox dens.

‘There’s something there!’

LD

Did it turn out as you had hoped?

The narrative ended up being simpler. Initially, I wanted to include a lot and provide extensive background information. But I found that wasn’t the essence of the film. It’s really about paying attention and what La Friche reveals, not what I want to say about it. By naming the place at the beginning and letting the place speak for itself for the rest, it became a universal green space near an urban landscape. This also gave my story a clear direction and message.

LD

The triangle of interaction: you as filmmakers with the place, you as filmmakers with your own tools, and those tools in translating the place. That triangle works fascinatingly.

It was a fun field to film from, working with the richness and limits of those three aspects, and exploring the boundaries of each.

LD

What is the most important thing you learned as a creator?

How to be transparent in your creative process, and that it can be a playful endeavor. Keeping both playful and reflective – “what are we doing?” Taking time. With a small crew of a maximum of two per visit, we had the flexibility to do things our way. It starts with a very simple premise, but to keep it engaging and interesting, you have to explore and open up many avenues.

LD

What feedback helped you move forward?

Someone mentioned that my introduction was long and unclear about the nature of the film. People might expect twenty minutes of pretty pictures. That’s why I included elements that suggest what you’re seeing, like the clear “Zoom H6” in the sound and “here it comes, start it.” It provides a guide. The creators also appear in it. If I hadn’t edited those abstract images properly, it would have been quite confusing for viewers.

LD

Other viewers immediately understand what they’re watching because of the narrative you’ve set up, but the surprise remains. The answer from that place.

It feels like La Friche is shouting out in the end, ‘This is me, now look at it.’ I thought it was good to end on that note. We included another shot after that one to come back down.

LD

What do you think of what you’ve made?

I think I created a portrait of a place, a conversation rather than just talking about that place. I hope I succeeded in that. A portrait in the form of communication. I like that it comes from both directions.

Text by Laurent Derycke