“The unraveling of a torment: you have to begin somewhere”

An exchange of thoughts between Eva Jacobs, Jana Coorevits, and others. Eva opens the conversation using the words of others, Jana picks up the thread while looking at Eva’s work.

“The unraveling of a torment: you have to begin somewhere:

the colour blue, the damage is repairable,” wrote Louise Bourgeois.

“Here is the beginning of necessary violence,” responds Kathy Acker.

Jana Coorevits

“The damage is repairable” – I think of your frayed black jumpers. The woven photograph of your mother hanging above them moved me. What affected me most was the act of weaving itself: slowly and carefully building an image, undertaking a journey with a photographic image, and in doing so, giving it new meaning.

Your mother’s gaze was once directed at the camera. Yet during the weaving process, as you reinterpreted the photographic image, her gaze gradually shifted towards you. You look at each other. For me, this dialogue or connection is created through the action you take in making your image.

“I was once foolish enough to believe knowledge would clarify, but some things are so gauzed between layers of syntax and semantics, behind days and hours, names forgotten, salvaged and shed, that simply knowing the wound exists does nothing to reveal it.” (Ocean Vuong)

When I look at your work, it feels as though I gain access to a mental landscape, where images aren’t formed through language and thought. Is weaving for you a way of revealing?

Every thread I wove began to introduce itself to me as a new part of my mother that I needed to identify and acknowledge. It was as if, through this process, I was attempting to unfold her existence. By weaving the threads into a new, ordered pattern, I felt like I was indeed revealing her. As though this was my way of getting to know her better and giving her a more comfortable place in my life.

Unravelling my mother’s mannerisms to their deepest depths turned out to be an impossible task. Yet, for a brief moment, I thought I could manage it. Slowly, weaving became a journey into the wilderness that my mother represents.

Weaving meant confronting her. Only on days when I was filled with pride could I do this without debris. The woven pieces formed into physical and silent testimonies of a grieving process. Each piece now presents itself as a portrait of my mother, censored by my own gaze. It’s impossible to capture her without myself, let alone understand her.

“There is a process of self-censorship, perhaps unconscious, of what should be spoken and what remains unsaid, what should be seen and what is left for interpretation,” says Iman Mersal in the book How to Mend: Motherhood and Its Ghosts.

Weaving became my language of processing. In that sense, weaving was emotionally heavy. I had to begin by looking my mother in the eye. Naming our relationship with the right words. Picking at hardened scabs. Unravelling mended jumpers. Accepting the damage and hemming it in. This, it turns out, is the real task.

“How do other mothers appear to their children? What is it you see, or don’t see, in a picture of a mother who belongs to you?” This is the question Mersal asks herself. It’s a question that lingers steadfastly in my mind. “How do mothers appear to their children?”

My mother looks at me straight and piercingly in the face.

JC

“Today I’m wearing my mother’s shirt.

Today I’m wearing my mother’s dress.

Today I’m wearing my grandmother’s scarf.”

In a journal, you document how you wear your mother’s and grandmother’s clothes for a while. After your grandmother’s passing, you spend four days in her house, wearing her clothes and lying in the same positions she often assumed during your conversations. You place the camera where you once sat during those talks.

In response to the question, “How do mothers appear to their children?” you seem to be formulating an answer through a game of gazes, where you embody one of the threecharacters in your story. You not only explore how it feels to receive their gaze, standing in their shoes and wearing their clothes, but also how it feels to observe them from a distance, with a medium (photography, weaving) acting as a buffer. Whether you are looking at them or at yourself becomes blurred; you merge into a single body.

InWhat I Loved, Siri Hustvedt writes: “The world passes through us – food, books, pictures, other people. (…) ‘Mixing’ is a key term. It explains what people rarely talk about, because we define ourselves as isolated, closed bodies who bump up against each other but stay shut. Descartes is wrong. It isn’t: I think therefore I am. It’s: I am because you are.”This merging becomes tangible in your work. When I look at the image above, I don’t just think of you and your grandmother, but of all the mother-daughter relationships that came before. Of the conversations that could or couldn’t take place, and how each story leaves out as much as it reveals.

“Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine. Meanwhile the world goes on.” (Mary Oliver)

I hear Jacques Douai singing:

“File la laine. Filent les jours. Garde ma peine et mon amour.”text: Jana Coorevits, visual artist

Seppe-Hazel LaeremanslectureAgendaArtistic activities

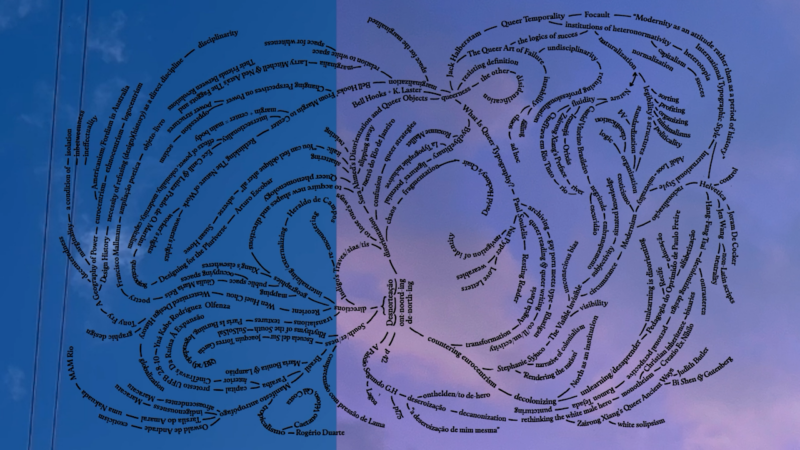

Seppe-Hazel LaeremanslectureAgendaArtistic activitiesGrains of Sand Like Mountains makes a bridge to another cultural island in Ghent. Seppe-Hazel Laeremans organises a collective reading at the exhibition in Kunsthal Gent and a collective gathering at the experimental art space Het Paviljoen. They invite you along on a walking tour from one space to another.

The afternoon will start by gathering in the exhibition Grains of Sand Like Mountains where a collective reading will happen, hosted by Laeremans. This performance will seep into a walking tour, and the event will end at Het Paviljoen with a moment for afterthoughts on the grass of the Bijloke site. Seppe-Hazel Laeremans is one of the residents of the project, Jumping Fences in Het Paviljoen.

The picnic will provide vegan-friendly snacks and drinks. The walking tour from Kunsthal Gent to Het Paviljoen will last around 30 minutes.

Seppe-Hazel Laeremans

Seppe-Hazel Laeremans (b. 2000) is a Belgian graphic designer, artist, writer, and editor currently based between Porto and Ghent. Their work has been featured in De Verffabriek (Ghent), Projectvierennegentig (Ostend), EKA GD Stand-in School (Berlin) and Bikini Books (Porto). Seppe-Hazel is currently one of the residents of Jumping Fences in Het Paviljoen, Ghent.

Lange Steenstraat 14

9000 Gent

thibault goudket, SGQ, Danzel’s Projects, AYATARU, Finding EmoconcertAgendaArtistic activities

thibault goudket, SGQ, Danzel’s Projects, AYATARU, Finding EmoconcertAgendaArtistic activitiesthibault goudket, 17:30 — Turbinezaal

Merging guitar loops with live electronic sounds that tickle the ear I’ll be taking the vulnerability of recording music on my own, in my home, to a live setting for the first time.

Thibault Goudket (gitaar, bas, electronics, drums)

SGQ, 18:30 — Kelderzaal

SGQ is a dynamic quartet driven by an unwavering passion and care for music. Ever curious, SGQ endeavors to find a sense of warmth and trust in the music and each other, creating a space of intense intimacy for the musicians and its audience.

Sam Goekint (drums), Jonas Paenen (piano), Tristan Tarras (double bass), Elly Brouckmans (altsax)

Danzel’s Projects, 19:30 — Turbinezaal

My master's thesis will consist of a collection of projects in which I am active. During my performance, I will make a long crescendo from an intimate set to a banging band that will make you dance.Frank Boddin (vocals, keys), Marte Truyers (vocals), Stan den Heijer (vocals, guitar), Dave Lantsoght (guitar), Robin Vantomme (keys), Inigo Grau (bass), Jef Denissen (bass) and Bartas Boots (alt-sax).

AYATURU, 20:30 — Kelderzaal

AYATARU is the world created by drummer/producer Thijs van Scharen. He blends his love for beats, beat making and deep groove, with influences ranging from UK breakbeat and the avant-garde hiphop scene of LA, IDM and spiritual jazz. All wrapped up in rich textures and warm sounds. Catching the moment as it comes and create new worlds where the head nod and dancing meets the deep thoughts within. This collage where each composition is a different scene, a different vibration can be viewed as a film – where the listener is guided through and can create their own narrative.

Ee (EWI, sax, bass clarinet), Alexis Boone (keys), Sander Huys (bass), Thijs van Scharen (drums)

Finding Emo (Tibo Polleunis), 21:30 — Turbinezaal

A once in a lifetime experience…literally! For his final school project Tibo Polleunis will channel his inner sad boy straight out of a 1999 high school movie. They’re here to break hearts and fuel your existential crisis! Dresscode = black.

Tibo Polleunis (drums), Edward Kuijken (bas), Tim Toegaert (gitaar), Achilles De Raedt (gitaar), Vincent-Laurens Seys (vocals)

Kraankindersstraat 2

9000 Gent

Screenings film and animation film, KASKcinemafilmAgendaArtistic activities

Screenings film and animation film, KASKcinemafilmAgendaArtistic activitiesAt KASKcinema, there will be screenings of the graduation works film and animation film between 27 and 30 June.

THU 27.06

- 12:00 FILM 1

- 14:00 ANIMATION 1

- 16:00 FILM 3

- 18:00 ANIMATION 2

FRI 28.06

- 12:00 FILM 4

- 14:00 FILM 2

- 16:00 FILM 5

- 18:00 VISUAL ARTS

SAT 29.06

- 12:00 ANIMATION 2

- 14:00 FILM 3

- 16:00 FILM 4

- 18:00 FILM 1

SUN 30.06

- 12:00 FILM 5

- 14:00 VISUAL ARTS

- 16:00 ANIMATION 1

- 18:00 FILM 2

ANIMATION 1

Ieva Lība Ratniece, Wandering dot and the blank square page universe

Rune Callewaert, The Masque of the Red Death

Joeri Joris, De Kruikenman

Hasan Pastacı, Sphere Supreme

Danae Zegers, Saudade

Chloé De Backer, Heart to Heart

Gitte Le Bruyn, Gyrograph

ANIMATION 2

Stijn van Staveren, PLAK

Marthe Verschaeve, Afgewezen. Aanname van objecten

Stéphanie El Khoury, Filigrane

Babette Goemare, Opia

Elie Vindevogel, De Eenzame Roker 2

Helene Van den Broeck, Tuesday, September 21 - Tuesday, June 21

FILM 1

Mathilda Vermeulen, Every inch is covered

Luzia Johow, Droomadom

Anaïs Kaboré, Touch Me With Your Eyes

laura persijn, underneath it flickers

FILM 2

Lisa Coene, Almost There

Sélin Van Laethem, Fuga del Gato

Lore Loyens, Where the Black Sand Burns

FILM 3

Bao Van Hoe, Shadowplay

Hazel Dupont, Kerberos

Alexander Goesaert, At Least We Have Eachother

FILM 4

Noah Berhitu, Statues Rule the Waves

FILM 5

Asel Backhakova, Test 1

Isa de Grood, Een kat, een hond, twee konijnen en acht mensen

Luca Fetnaci, Sidi

VISUAL ARTS

Leon Decock, Oh Look!

Sofie Roelants, sleeping sun rise

Manon Jejcic, Le Jaune et le Bleu

Sarah Chapuis, Peau Neuve

Jules Mathôt & Cinemaximiliaan, In the Palm of My Hand

Cloquet

Godshuizenlaan 4

9000 Gent

Expo & performances Graduation 2024expoAgendaArtistic activities

Expo & performances Graduation 2024expoAgendaArtistic activitiesSpread out over the Bijloke campus, you can discover the work of students in photography, graphic design, autonomous design, fine arts, textile design, fashion, musical instrument making, interior design, landscape and garden architecture, landscape development, digital design and development, curatorial studies, educational master in audiovisual and visual arts and the educational master in music and performing arts.

PERFORMANCES

Nora Allegaert, The wormsuit

29 & 30.06.24, 14:00-18:00

Try out the wormsuit in the company of the artist.

burger service (featuring Hilke Walraven), concert

27.06.24, 22:30———————entrance Cloquet

Suzanne Cleerdin, Progress written in the stars

27.06.24, 15:00

28.06.24, 15:00

29.06.24, 12:30

An audio-visual performance by

Suzanne Cleerdin, with Shadi Alaiek

Scenography: Eline Harmse

Audio technician: Isaac Moss

Paul Demets, Het woord niet gebroken

27.06.24, 19:00———————-auditorium Horta

Poems and prose excerpts by Palestinian and Ukrainian authors.

Marthe Huyse, Tafel voor Zes

No set hours———————-entrance hall KIOSK

Seppe-Hazel Laeremans, To Settle, To Unsettle

30.06.24, 15:00———————-Kunsthal Gent

Jumping Fences, Closing event

27.06.24, 18:30———————-Het Paviljoen

Jeandré Eli José, ANGELIC – IN&OUT

Performance (±60 min)

Facebook event

27.06.24, 20:30

29.06.24, 18:30

30.06.24, 18:30

With: Eva Calderone, Pingkan Polla, Rinus Martha Chaerle, Anthony Chang, Ashley Van Poucke & Jeandré Eli José

Partytent Art Center

Grand Opening in and around Bijlokesite

27 – 30.06.24

27.06, 19:00 at Horta Garden: talk with Liesbeth Huybrechts, Danielle van Zuijlen, Zeger Vetters, Mark van Hoek and participating artists.

@partytentartcenter for more information

With support of Stad Gent

Peter van de uitleendienst, Dirty Old … Town

27.06.24, 18:30———————-Terrace KASKcafé

Sailah Soundsystem, Outdoor Roots Reggae daytime session

27.06.24, 12:00-19:00———————–Horta garden

Naomi James Schatteman, INVITATION FOR CHANNELING A LIMINAL STATE (Preliminary methods and outlines for choreographic and spatial practices).

Performance (±45 min)

Reservations

27.06.24, 15:00 ———————- Atelier GBPAU.0.263 (next to tramzwart)

28.06.24, 16:30, 19:00 ———————- Atelier GBPAU.0.263 (next to tramzwart)

29.06.24, 14:00, 16:30 ———————- Atelier GBPAU.0.263 (next to tramzwart)

30.06.24, 16:30, 19:00 ———————- Atelier GBPAU.0.263 (next to tramzwart)

@naomijamesschatteman for latest updates

Mieke (Mik) Schelstraete, Experts are in the dark

27.06.24, 20:30———————-auditorium Horta

Ine Vanlitsenborgh, De Receptie

27.06.24, 18:00——————————Zwarte Zaal

K4SKPalestine, Screenprinting

27.06.24, 13:00------------------------------Esplanade Marissal

K4SKPalestine, Silent march

27.06.24, 17:30------------------------------Bijlokehof

Lucrecia Wang Jaramago, It is about time

Reading (±25 min)

27.06.24, 13:00, 15:00, 17:00, 19:00 ---------------------- Cirque

28.06.24, 13:00, 15:00, 17:00, 19:00 ---------------------- Cirque

29.06.24, 13:00, 15:00, 17:00, 19:00 ---------------------- Cirque

30.06.24, 13:00, 15:00, 17:00, 19:00 ---------------------- Cirque

approx. 10 spaces per session

Fri, Sat, Sun, 12:00 – 20:00

Robin Lambrecht, Andreas Duchi, Jeane Flo, IKARO, BRINESconcertAgendaArtistic activities

Robin Lambrecht, Andreas Duchi, Jeane Flo, IKARO, BRINESconcertAgendaArtistic activitiesRobin Lambrecht, 17:30 — Turbinezaal

The music of Robin Lambrecht and his band is a fusion of post-rock and jazz, through set compositions with room for emotive improvisation. The band he gathers under his own name is a group of people close to his heart, which is key to sincerely conveying and sharing emotion within his compositions. The focus is on lyrical themes, the blurred line between composition and improvisation and to what extent instrumental music can be narrative. Robin's compositions have been described by others as cinematic, atmospheric, narrative, energetic and to dream away. This sums up what the project aims at; to make the listener dream away, both in a live and listening context, as would happen with a good book, series or film.

Roel Delplancke (drums), Stanzi Cresens (cello), Jesse Vandecaetsbeek (keys), Ruben Van Hijfte (bass), Robin Lambrecht (guitar)

Andreas Duchi, 18:30 — Turbinezaal

In an intimate setting, Andreas Duchi delves into the soulful resonance of the bass guitar. Whether sculpting melodies solo or in duet, his music beckons the listener into a realm of tenderness and warmth, imbued with a touch of mystique that lingers in the air. Join him on a journey where each strum is an invitation to explore the depths of musical expression.

Andreas Duchi (bass), Didier Deruytter (vocals)

Jeane Flo, 19:30 — Turbinezaal

Get ready for a musical explosion with Jeane Flo! Our band delivers a dynamic mix of powerful riffs, refreshing melodies and irresistible grooves that grab you from the very first chord. With a unique combination of influences from classic rock, funk and hard rock, we bring a contemporary twist to the genre. Get carried away by our energetic sound and experience a musical journey with Jeane Flo!

Maxime Aerts (guitar), Catherine Denayer (drums), Noah De Matos (bass), Lucas Heytens (keys), Heleen Desmet (lead vocal), Lisa Baert, Louke Vandorpe, Indira Bergmans (backing vocals)

IKARO, 20:30 — Kelderzaal

Ikaro was born from a shared love of (ethio)jazz, dub and afrobeat. Throw into the mix: feathery horns with a solid jazz background, a generous dash of rakia (fruit brandy, popular in the Balkans), a lavish dose of cutting guitar and bass riffs and energetic percussion, and a highly danceable and slightly mysterious sound is born. They performed on the Jonge Wolven stage at Trefpunt during the past Gentse Feesten, were among the East Flemish selection for Sound Track and whistlingly unite many jazz and rock lovers along the way.

Nele Vernaillen (flute), Cedric Haeck (bass), Kamiel Bossuyt (guitar), Bartas Boots (saxophone and kalimba), Oya Bakiroglu (darbuka, conga, bongo), Ferre Heyvaerts (drums)

BRINES, 21:30 — Turbinezaal

When Justine Rotsaert and Dave Lantsoght traded the Knokse beach for the rehearsal room, it soon produced sparks, which Dave skilfully channelled into fat beats and cutting electric guitar work. Combined with Justine's sultry voice, they arrived at a unique sound that no fresh North Sea dive could match.

Dave Lantsoght (guitar, vocals, synths), Justine Rotsaert (vocals, synths), Jens Dolleslagers (live mixing)

Kraankindersstraat 2

9000 Gent

Xiaocheng Wang, Oscar Murillo Ardanuy, Yassine Posman, Luís Santos Melo, MIRY Concert hallconcertAgendaArtistic activities

Xiaocheng Wang, Oscar Murillo Ardanuy, Yassine Posman, Luís Santos Melo, MIRY Concert hallconcertAgendaArtistic activities- Xiaocheng Wang, 15:00 — clarinet

- Oscar Murillo Ardanuy, 16:30 — clarinet

- Yassine Posman, 18:00 — clarinet

- Luís Santos Melo, 20:00 — clarinet

Our classical music students hone their skills until they are ready for their exam recitals. You can attend this joyous occassion, as the exam concerts of master’s students of classical music and composition are open to the public. All concerts take place in our very own MIRY Concert Hall.

9000 Gent

Wannes, Nautilus, I MALATI, Ruben Van Hijfte (feat. HAVAN), Toon Putteman TrioconcertAgendaArtistic activities

Wannes, Nautilus, I MALATI, Ruben Van Hijfte (feat. HAVAN), Toon Putteman TrioconcertAgendaArtistic activitiesWannes, 17:30 — Turbinezaal

Wannes, as the only band member, will transform the stage into a musical laboratory where groovy beats and the sound of his guitar merge into a unique improvisational experience. During this performance, Wannes will take the audience on a journey where he utters every note like a story and considers every beat an adventure. Prepare for an evening full of surprises and musical discoveries, as Wannes is ready to transcend the boundaries of the familiar and add a new dimension to the concept of "live performance".

Wannes (Guitar, Bass, Keyboard, Drum computer)

Nautilus, 18:30 — Kelderzaal

Nautilus is four musicians embarking on a vessel exploring their inner self. The music written is a reflection on certain emotions or conditions one might encounter and is a personal musical interpretation of such feelings and struggles. Life is unpredictable and we must be prepared for any circumstances good or bad coming our way. The Nautilus created by Jules Verne is now heading towards yet another mysterious universe. The only one place human beings often fear. The inner self.

Arnaud Guichard (Tenor Sax), Leonard Steigerwald (piano), Otto Kint (double bass), Mattia Gobbo (drums)

I MALATI, 19:30 — Turbinezaal

The experimental octet I Malati brings on the stage an intriguing blend of rock suggestions and free improvisation, poetry and brutality. It is evidently a complex language with intricate layers of sound, rich thematic variety and colorful kaleidoscopic weaves of melodic and rhythmic textures. However, the obliqueness of the meta-theatrical voice, the melodic sweetness and the fiery projection of the blowers, the roughness of the distorted guitar lead the listener to a raw human dimension, providing a fascinating contrast and enriching the emotional narration of the music.

Nathan Isahakyan (spoken voice), Luís Melo (clarinet), Loïs Pluymers (alto), Arnaud Guichard (tenor), Gonçalo Oliveira (electric guitar), Francisco Morato (electric bass), Mattia Gobbo (drums), Aleksandar Škorić (percussions).

Ruben Van Hijfte (feat. HAVAN), 20:30 — Kelderzaal

Rhythmic smiles, heartfelt lyrics, and a hefty dose of Hindustani Classical to fill up your love tank ^^.

Hanne Dollery (piano, guitar, vocals), Robin Lambrecht (guitar), Nathan Goessens (drums), Oya Bakiroglu (doholla), Seppe Vermeiren (sitar)

Toon Putteman Trio, 21:30 — Turbinezaal

Toon believes that the best music is created in the moment of total surrender. To reach this point, there must be a rock-solid form of trust and curiosity within a group. For this, he looked for musicians who have spent countless hours in rehearsal rooms with a passion for improvisation and a singular vision. Spurred on by his current teacher Lander Gyselinck, Toon writes compositions that are a reconciliation between contemporary jazz, free improvisation and the occasional touch of electronica. Each composition is seen as a blank canvas. In it, they search for the limits of both the musical framework, their own creativity, physical possibilities, the musicians' ears and the audience's ears. Expect an adventurous concert in which three young musicians, connected by their love of jazz, interact, improvise and create through their instruments.Toon Rumen (bass), Thibaut Deryckere (piano), Toon Putteman (drums)

Kraankindersstraat 2,

9000 Gent

Avant-premières film and animationfilmAgendaArtistic activities

Avant-premières film and animationfilmAgendaArtistic activitiesSphinx Cinema is the decor where master students of audiovisual arts project their graduation works into the world. Proudly, they present their fiction films, documentaries, video works and animated films. On Tuesday 25 June, you can watch the new batch of films and animations.

If you cannot attend the avant-premières, you can visit KASKcinema on the Bijloke campus from 27 June onwards. The films of the graduating master students will be screened there until 30 June.

PROGRAMME

- 17:00 Zaal 1 > FILM 1

- 17:30 Zaal 2 > FILM 2 +Live projection Test 1, Asel Bakchakova

- 17:30 Zaal 3 > ANIMATION 1

- 19:00 Zaal 1 > FILM 3

- 19:15 Zaal 3 > FILM 4

- 19:30 Zaal 2 > ANIMATION 2

- 21:00 Zaal 1 > FILM 2

- 21:00 Zaal 2 > FILM 1 +Live projection Test 1, Asel Bakchakova

- 21:15 Zaal 3 > ANIMATION 1

- 22:45 Zaal 3 > FILM 3

- 23:00 Zaal 1 > FILM 4

- 23:00 Zaal 2 > ANIMATION 2

ANIMATION 1

Ieva Lība Ratniece, Wandering dot and the blank square page universe

Rune Callewaert, The Masque of the Red Death

Joeri Joris, De Kruikenman

Hasan Pastacı, Sphere Supreme

Danae Zegers, Saudade

Chloé De Backer, Heart to Heart

Gitte Le Bruyn, Gyrograph

ANIMATION 2

Stijn van Staveren, PLAK

Marthe Verschaeve, Afgewezen. Aanname van objecten

Stéphanie El Khoury, Filigrane

Babette Goemare, Opia

Elie Vindevogel, De Eenzame Roker 2

Helene Van den Broeck, Tuesday, September 21 – Tuesday, June 21

FILM 1

Mathilda Vermeulen, Every inch is covered

Lisa Coene, Almost There

Luca Fetnaci, Sidi

FILM 2

laura persijn, underneath it flickers

Anaïs Kaboré, Touch Me With Your Eyes

Alexander Goesaert, At Least We Have Eachother

FILM 3

Sélin Van Laethem, Fuga del Gato

Noah Berhitu, Statues Rule the Waves

Bao Van Hoe, Shadowplay

FILM 4

Luzia Johow, Droomadom

Hazel Dupont, Kerberos

Isa de Grood, Een kat, een hond, twee konijnen en acht mensen

Lore Loyens, Where the Black Sand Burns

i.c.w. Sphinx Cinema

Sint-Michielshelling 3,

9000 Gent

Ano Matchavariani, Márta Soós Borbála, Timothy Veryser, MIRY Concert hallconcertAgendaArtistic activities

Ano Matchavariani, Márta Soós Borbála, Timothy Veryser, MIRY Concert hallconcertAgendaArtistic activities- Ano Matchavariani, 17:00 — voice

- Márta Soós Borbála, 18:30 — voice

- Timothy Veryser, 20:00 — voice

Our classical music students hone their skills until they are ready for their exam recitals. You can attend this joyous occassion, as the exam concerts of master’s students of classical music and composition are open to the public. All concerts take place in our very own MIRY Concert Hall.

9000 Gent

Adhami Antonio, Shiu Wai Yau, Melvin Choi, MIRY Concert hallconcertAgendaArtistic activities

Adhami Antonio, Shiu Wai Yau, Melvin Choi, MIRY Concert hallconcertAgendaArtistic activities- Adhami Antonio, 11:00 — composition

- Shiu Wai Yau, 15:00 — composition

- Melvin Choi, 18:00 — composition

Our classical music students hone their skills until they are ready for their exam recitals. You can attend this joyous occassion, as the exam concerts of master’s students of classical music and composition are open to the public. All concerts take place in our very own MIRY Concert Hall.

9000 Gent

Closing Statement Drama FestivaldramaAgendaArtistic activities

Closing Statement Drama FestivaldramaAgendaArtistic activitiesKASK DRAMA: CLASS OF 2024 is here.

As a finale to the DRAMA FESTIVAL at Graduation 2024, and also to our master's programme, all masters will present a short farewell show together: a performance medley filled with all the form and content impossible to fit into a speech.Afterwards, you can exchange your filled savings card for a glass of cava. (Savings cards can be found at the box office of each master's project).

credits

- Bavo Buys

- Emma Verstraete

- Fiene Zasada

- Joshua Smits

- Malique Fye

- Maria Zandvliet

- Melody Van Gompel

- Renée Leerman

- Robbe Vandenven

- Senne Paulussen

- Sophie Anna Veelenturf

- Toon Acke

Nieuwpoort 31/35

9000 Gent

Shows Graduation modeeventAgendaArtistic activities

Shows Graduation modeeventAgendaArtistic activitiesFashion students from KASK & Conservatorium present their graduation projects during 2 shows at the Arsenal site. They will add a piece of history to this old railway workshop at 17:00 and at 21:00.

Bachelor students from all years show on the catwalk what they have produced this academic year. The icing on the cake are the graduation collections of the master students.

From 21 to 23 June, you can visit the exhibition of fashion and textile design students at the same venue.

You only need to buy a ticket for the shows on Saturday 22 June, the exhibition is free to enter.

Shows Graduation modeeventAgendaArtistic activities

Shows Graduation modeeventAgendaArtistic activitiesFashion students from KASK & Conservatorium present their graduation projects during 2 shows at the Arsenal site. They will add a piece of history to this old railway workshop at 17:00 and at 21:00.

Bachelor students from all years show on the catwalk what they have produced this academic year. The icing on the cake are the graduation collections of the master students.

From 21 to 23 June, you can visit the exhibition of fashion and textile design students at the same venue.

You only need to buy a ticket for the shows on Saturday 22 June, the exhibition is free to enter.

Shows Graduation modeeventAgendaArtistic activities

Shows Graduation modeeventAgendaArtistic activitiesFashion students from KASK & Conservatorium present their graduation projects during 2 shows at the Arsenal site. They will add a piece of history to this old railway workshop at 17:00 and at 21:00.

Bachelor students from all years show on the catwalk what they have produced this academic year. The icing on the cake are the graduation collections of the master students.

From 21 to 23 June, you can visit the exhibition of fashion and textile design students at the same venue.

You only need to buy a ticket for the shows on Saturday 22 June, the exhibition is free to enter.

a Disarming Design workshoplectureAgendaArtistic activities

a Disarming Design workshoplectureAgendaArtistic activitiesA reflective afternoon with Disarming Design for Palestine centres on developing infrastructures for solidarity through design. The session includes a workshop where participants collectively create graphic statements for a 'Fair Glossary' exhibition, focusing on design infrastructures, language, and fair trade. The event wraps up with a film screening that offers insights into the product-making processes and their narratives.

- 14:30-18:00, an ongoing conversational pop-up shop with Sulaiman Saleh

- 15:00-18:00, Unpacking notions and building threads, a Disarming Design workshop with Annelys de Vet

- 19:00, United Films for Palestine screening, Picasso in Palestine by Rashid Masharawi (52')

Disarming Design from Palestine

Disarming Design from Palestine (DDfP) is an independent non-profit organisation that operates as a design label and learning platform. Their mission is to foster thought-provoking design from Palestine by developing and distributing useful products that share poetic and political statements. Often rooted in experiences from everyday life in occupied Palestine, the items serve as cultural artefacts that catalyse conversations. Disarming Design is a collective based in Sint Pieters Leeuw, Belgium. Their work has been featured in De Appel, Amsterdam, Decoratelier, Brussels and Pianofabriek, Brussels.

United Screens for Palestine

United Screens for Palestine is an open and decentralised collective of programmers, cultural workers and venues. They are responding to the paralysis brought about by the ongoing genocide as well as the increasing policing, censorship and criminalisation of everything Palestinian. They aim to make each screening a space for conversation, learning and most of all, mobilisation. And they firmly believe that to present these films is to insist that witnessing is an active process, far beyond the act of watching. Ultimately, they build on long-standing global film initiatives which serve as platforms for substantive discussions and an earnest exploration of the historical narrative of Palestine.

deel van het publiek programma rond de groepstentoonstelling 'Grains of Sand like Mountains', gecureerd door de studenten curatorial studies 2023-24

Lange Steenstraat 14

9000 Gent

Adriël Cantamessi, MIRY Concert hallconcertAgendaArtistic activities

Adriël Cantamessi, MIRY Concert hallconcertAgendaArtistic activitiesOur classical music students hone their skills until they are ready for their exam recitals. You can attend this joyous occassion, as the exam concerts of master’s students of classical music and composition are open to the public. All concerts take place in our very own MIRY Concert Hall.

9000 Gent

LINKSE GAATJES, KASK DramadramaAgendaArtistic activities

LINKSE GAATJES, KASK DramadramaAgendaArtistic activitiesS. is een linkse trut, een Becky, een lief DeMorgen-meisje. Ze drinkt haar koffie met havermelk en koopt alleen haar ondergoed nieuw. En ze houdt van daten. “Blijf swipen, zo leren we je smaak kennen!” Maar wat als je rechts per ongeluk niet naar links swipet, maar naar rechts? Swipet rechts, links altijd naar links? Soms is links en rechts toch een match, en S. ontmoet A., B., en C.

Ik wil je zo hard doen wanneer we niet overeenkomen.

Wil je in mijn mond spugen?

Je hebt gelijk dat je me naar rechts hebt geswiped.

Je hebt gelijk dat ik soms een beetje fel ben.

Je kent me eigenlijk al door en door.

Daarom mis ik je ook zo hard.

S. had een date burn-out en besloot haar leven te beteren en de wereld te depolariseren. Ze is namelijk een heel goed mens. Ze nam veertien interviews af, kwam kletsen op de zetel bij ‘de rechtse man’ in zijn vele soorten en maten: van vissers tot politici tot mariniers. Ze ontdekte dat vrouwen soms ook rechts zijn (zij vonden de Barbie film wel goed gelukt). Ze dronk thee met politieke Romeo en Julia’s in Nederland en België en sprak over hartzeer met gepolariseerde exen. En ze sprak ook zichzelf.

"Twee geloven op een kussen, daar slaapt de duivel tussen. En wie zegt dat ik een kussen wil delen? Ik wil mijn eigen fucking kussen."

CREDITS

- play, concept & text: Sophie Anna Veelenturf

- mentors: Kristien De Proost & Thomas Bellinck

- direction: Doris de Vries

- musical & comical coaching: Valentina Tóth

- dramaturgy: Remi Cosijn & Doris de Vries

- productional assistance: Remi Cosijn

- image: Charlotte Jodogne

- (image)technical and auditory support: Maaike Jaspers, Charlotte Jodogne

- photos: Juliette de Groot

- special thanks to the interviewees

- extra thanks: KASK & Conservatorium, VIERNULVIER, De Kazematten, Gouvernement, CAMPO, Pepijn Huysman, Jana De Kockere, Martha Balthazar, Frederik Le Roy, Bardia Mohammad, Valerie Desmet, Sjoerd Koolma, kunstencentrum BUDA & fellow students

- with the support of DeAuteurs

Kazemattenstraat 17,

9000 Gent

22.06.2024, 18:00

Graduation fashion and textile designexpoeventAgendaArtistic activities

Graduation fashion and textile designexpoeventAgendaArtistic activitiesFashion students from KASK & Conservatorium present their graduation projects during 2 shows at the Arsenal site. They will add a piece of history to this old railway workshop at 17:00 and at 21:00.

From 21 to 23 June, you can visit the exhibition of fashion and textile design students at the same venue.

You only need to buy a ticket for the shows on Saturday 22 June, the exhibition is free to enter.

22.06, 11:00 – 23:00

23.06, 11:00 – 18:00

Free entry

Brusselsesteenweg 602

9050 Gent

FoyerTV | S1:E1 | Pilot, KASK DramadramaAgendaArtistic activities

FoyerTV | S1:E1 | Pilot, KASK DramadramaAgendaArtistic activitiesFive theatre-makers and a camerawoman try to provide an answer to an excess of content-less pastime through a sitcom about twenty-somethings. As they fight content with more content, the line between fact and fiction blurs. With Pilot, FoyerTV touches on the growing sense of anxiety in our time; fear of being forgotten, of missing something, of being expendable or unsuccessful. In this way, FoyerTV portrays a generation immersed in the images that surround them: from home video to Hollywood, from philosopher Mark Fisher to Friends.

Subscribe now to enjoy this live multicam event!

FoyerTV is a metamodern instagram account managed by a changing group of theatre makers who create reports around performances in the foyer.

On 22.06.2024, the performance will be followed by a subsequent 'closing statement' for the drama section of Graduation 2024.

Credits

- by & with: Esther van der Wel, Dagmar Dierick, Judith Engelen, Pieter van Dijk & Toon Acke

- camera: Alejandra Rogghé Pérez

- dramaturgy: Milan Van Bortel & Quinty De Vries

- production: Quinty De Vries

- technics: Ika Schwander

- technical production: Flore van Sparrentak

- scenography: Femke Florus

- costumes: Laura Lemaitre

- coaching: Jan Steen

- thanks to: Bauke Lievens, Simon De Winne, Wannes Gyselinck, Sven Ronsijn, Wim Helsen, Sebald van der Waal, Benoît Vanraes & onze medestudenten

- coproduction: KASK & Conservatorium, CAMPO & FoyerTV

- supported by: De Auteurs

Nieuwpoort 31/35

9000 Gent

22.06.2024, 20:30

Mad Mulish Man, Reinert Creve Trio, AntheconcertAgendaArtistic activities

Mad Mulish Man, Reinert Creve Trio, AntheconcertAgendaArtistic activitiesMad Mulish Man, 18:30

Inspired by both his classical and jazz background, Wodan Onkelinx wrote his compositions with movement in mind. Together with his talented band, he moves effortlessly from tranquillity to exuberance in the set. Expect a concert that feels like a trip straight ahead with an abrupt digression here and there.

Warre Van de Putte (tenor sax), Wodan Onkelinx (piano), Toon Rumen (double bass), Toon Putteman (drums)

Reinert Creve Trio, 20:00

The Reinert Creve Trio is the first project in which pianist Reinert Creve comes to the fore and shows his most personal side. Reinert's compositions are based on the principle that music arises from honesty and simplicity. This is reflected in the music the trio makes. Together with Toon Putteman on drums and Ruben Verbeeck on double bass, they explore how simplicity and lyricism can tell a story. In this way, they try to reflect their own interpretation within contemporary jazz in a way where improvisation and communication are central.

Reinert Creve (piano), Toon Putteman (drums), Ruben Verbeeck (double bass)

Anthe, 21:30

Originally from Bilzen in Limburg, Anthe Huybrechts — or Anthe for short — developed an unconditional love for the acoustic piano. Her way of playing and writing is influenced by her classical music training in her younger years. New influences, more experience and self-discovery fuel her musical world and lead to an intense, intriguing sound of her own with fairy-like melodies and personal lyrics in which influences such as Agnes Obel, Kate Bush, AURORA and even Björk can be traced. With her velvet voice, unforced piano playing and her own collection of samples and prepared piano sounds, Anthe immerses you in hopeful dreams.

Anthe Huybrechts (leadzang & toetsen), Luna Maes (achtergrondzang & toetsen), Stanzi Cresens (cello)

Romain De Coninckplein 2,

9000 Gent

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationGraduation 2024 Prize winners professional bachelors

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationGraduation 2024 Prize winners professional bachelors newsLees, kijk, luistereducationHannah De Bie, Erin De Schepper, Hans Druart, Luc Deschepperstudents and teachers landscape and garden design Mountain and school speak

newsLees, kijk, luistereducationHannah De Bie, Erin De Schepper, Hans Druart, Luc Deschepperstudents and teachers landscape and garden design Mountain and school speak articleLees, kijk, luistereducationThibault Goudketstudent jazz & pop Regulating emotions through music

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationThibault Goudketstudent jazz & pop Regulating emotions through music articleLees, kijk, luistereducationPartytent Art Center May those who feel inspired set up a party tent!

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationPartytent Art Center May those who feel inspired set up a party tent! articleLees, kijk, luistereducationlau persijnstudent film underneath it flickers

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationlau persijnstudent film underneath it flickers articleLees, kijk, luistereducationLuna Maesstudent jazz & pop I'm in lovey

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationLuna Maesstudent jazz & pop I'm in lovey articleLees, kijk, luistereducationLyn de Weijerstudent fotografie Dirkie

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationLyn de Weijerstudent fotografie Dirkie articleLees, kijk, luistereducationLucrecia Wangstudent autonomous design A Cabinet of Honesty

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationLucrecia Wangstudent autonomous design A Cabinet of Honesty articleLees, kijk, luistereducationBavo Buys and Maliqa Fyestudents drama “It is a strange realism, but it is a strange reality.”

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationBavo Buys and Maliqa Fyestudents drama “It is a strange realism, but it is a strange reality.” articleLees, kijk, luistereducationAbel Hartooni, Seppe-Hazel Laeremansstudents fine arts, graphic design To confuse, to disorient

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationAbel Hartooni, Seppe-Hazel Laeremansstudents fine arts, graphic design To confuse, to disorient articleLees, kijk, luistereducationHilke Walravenstudent vrije kunsten Wooden Days

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationHilke Walravenstudent vrije kunsten Wooden Days articleLees, kijk, luistereducationJules Mathôt, Cinemaximiliaanstudent educational master in audiovisual and visual arts “Instead of looking at the mirror, I was the one who was inside the mirror”

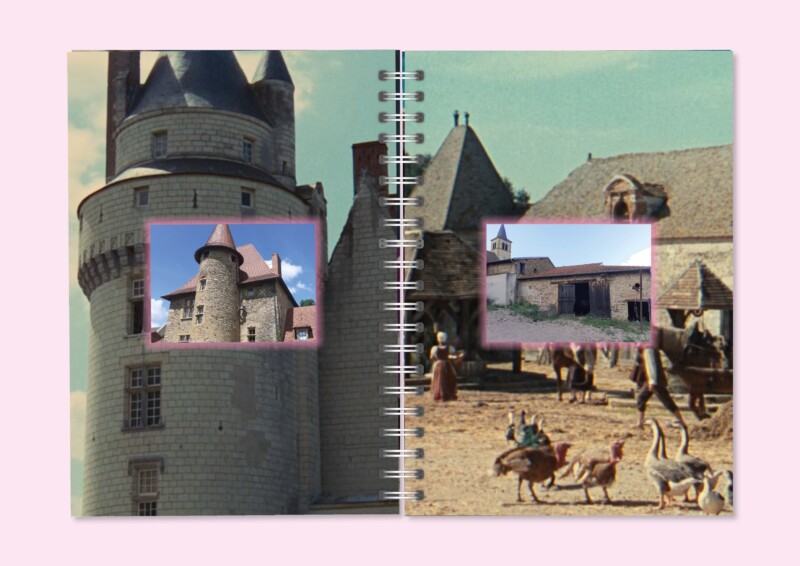

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationJules Mathôt, Cinemaximiliaanstudent educational master in audiovisual and visual arts “Instead of looking at the mirror, I was the one who was inside the mirror” articleLees, kijk, luistereducationSarah Chapuisstudent graphic design Peau d’Âne/Peau Neuve: the same, again, but different

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationSarah Chapuisstudent graphic design Peau d’Âne/Peau Neuve: the same, again, but different articleLees, kijk, luistereducationJosé Brandãostudent composition SanctuaryPortuguese composer José Brandão, 23, already has an impressive track record. He won several composition competitions and his piece Insurrection for solo piano was performed at Carnegie Hall. A promising beginning in the music world.articleLees, kijk, luistereducationGraduation 2024 Prize winners masters

articleLees, kijk, luistereducationJosé Brandãostudent composition SanctuaryPortuguese composer José Brandão, 23, already has an impressive track record. He won several composition competitions and his piece Insurrection for solo piano was performed at Carnegie Hall. A promising beginning in the music world.articleLees, kijk, luistereducationGraduation 2024 Prize winners masters newsLees, kijk, luistereducationGraduation 2024 drama festival

newsLees, kijk, luistereducationGraduation 2024 drama festival presentationLees, kijk, luistereducationGraduation 2024 classical music and composition

presentationLees, kijk, luistereducationGraduation 2024 classical music and composition presentationLees, kijk, luistereducationGraduation 2024 fashion and textile design

presentationLees, kijk, luistereducationGraduation 2024 fashion and textile design presentationLees, kijk, luistereducation Masterworks Vol. 13

presentationLees, kijk, luistereducation Masterworks Vol. 13 publicationLees, kijk, luistereducation

publicationLees, kijk, luistereducation